Month: December 2017

Forest Lanterns: Interactive Communities, Screening Solutions – Articles

Designing a Training with Participatory and Co-Creative Process

In my use of human-centered design (HCD) at Digital Green, I found that the inspiration and ideation phase in HCD as being completely intertwined. They can’t really be separated into two neatly divided phases. While we were trying to find a solution to the question ‘How can we enable field level workers to operate equipment confidently?’ – the processes we followed seemed to make no sense initially. In my previous blog, I had mentioned that it was the ‘messiness’ of the process that I really started enjoying, once I stopped being so hung up about ‘being systematic’. In that, what I both enjoyed and learnt the most was the freedom to follow your intuition and develop your own versions of methods, activities and processes.

While we used several of the conventional methods, such as interviews and secondary research, we also designed and conducted activities with users that we felt would get us closer to our design principles, and the solution. They could largely be bunched under 2 categories:

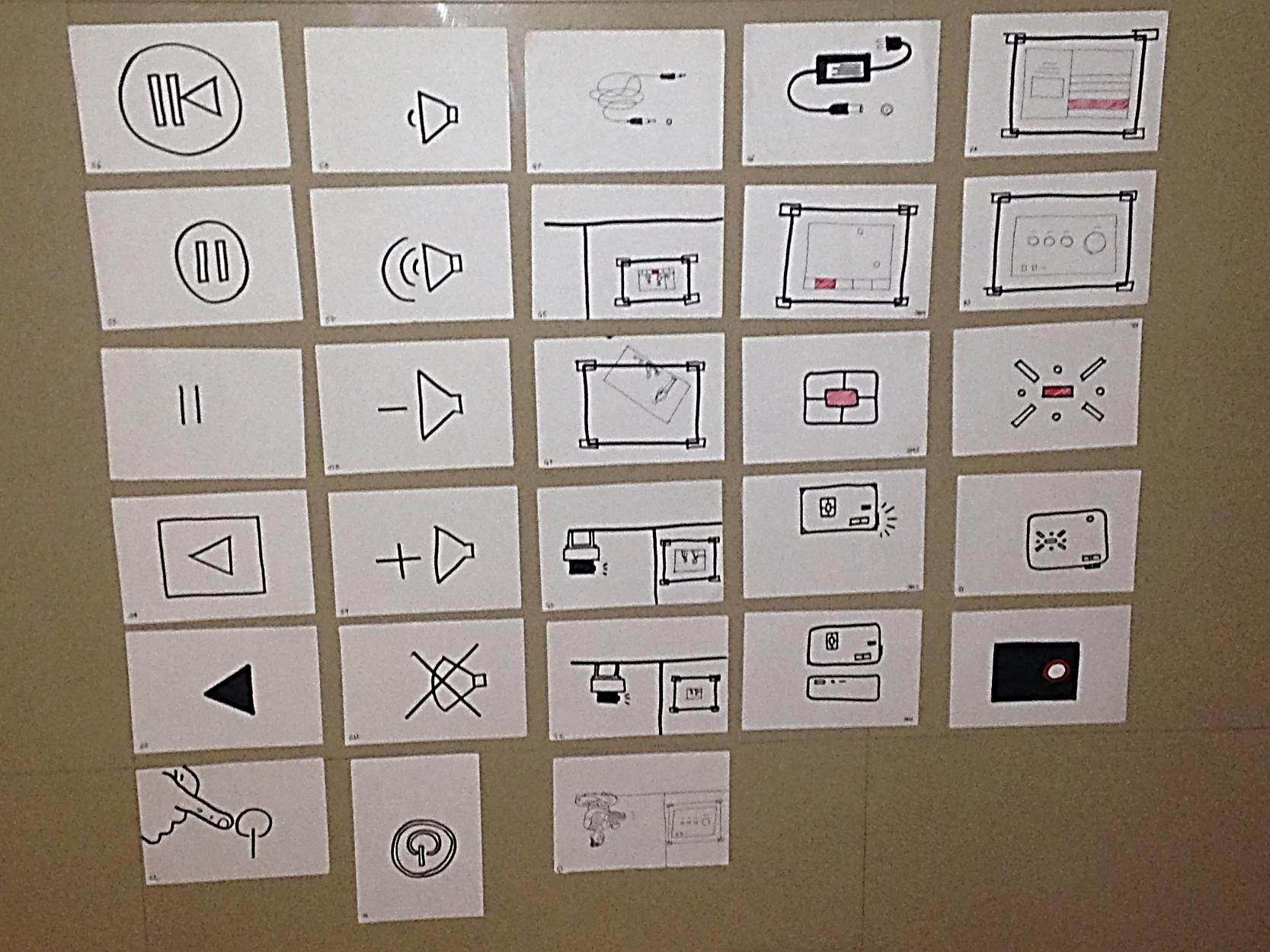

- Sharing what they know: We wanted our users, the field level workers, to learn the technical aspects of equipment operation really well. Therefore, it was important to understand the current experience and knowledge levels. What they shared revealed some very interesting insights. For example, that their ‘visual language’ was very different than ours. Or symbols on equipment, which we take for granted, is complex for them. They understood illustrations which show the context better than abstract symbols.

- Sharing their perspective: As trainers, we tend to see the learning process from our perspective and it is quite difficult to know the perspective of a person who learns differently from us. We saw this difference and wanted to understand from the field-level workers what is necessary for them to learn and how the learning process can be made easier. To reach there, we asked them to demonstrate how they would have made their peers learn, which revealed some critical aspects in their learning, for instance, the verbal language used in training – they used different terms to explain things than our trainers.

Under the above two categories, we conducted several activities, some of which used ‘co-creation’. I am using the term co-creation to define a process in which the end user creates at least some part of the prototype. It is a concept, not a tool or a method. Several methods can use the concept of co-creation. It could be a role-play that the users develop along with the designer, or a script for which they provide dialogues.

Participatory Video techniques and Co-creation

Of the different methods, I focus on participatory video here. Working with any participatory process, including video production, teaches you to learn from those who are at the center of the issue. Participatory video production is supposed to be driven by communities to communicate what they want to, and in a manner that they want. In co-creation models, though the user community is involved in the creation of a prototype/solution, they are usually not the ones driving it. Further, they communicate what the designer wants them to communicate. To make it more tangible, through participatory videos a community could have made a video about any issue they cared about. But as part of co-creation, we, the designers, asked them to make a video story specifically about equipment operation. The agenda was driven by us, not them.

Our team combined these two seemingly similar, but actually different concepts. We created several prototypes for different solutions that can together improve the training. The possible solutions included a training video, an illustrative handout and a team game that also works as a skill assessment. Initially, we thought that an obvious prototype of a video would be a role-play or a script. But then we thought – we have all the equipment and experience to make a video quickly. So, when prototyping, we used participatory video techniques for co-creation of a video. We asked the field level workers to develop the content for the video, which would show their peers how the equipment works. When they discussed the story with us, they had:

- Developed characters – who should be training whom (a senior field level worker will train a new joiner)

- Decided the context – when does one need the learning support (users usually find it difficult to operate equipment at the beginning),

- Defined the content – what are the essential operations to be learnt (a 15 step process)

We shot the prototype video with them, edited it the same evening and tested it the next day in a meeting of field level workers. Interestingly, most of the feedback that we got was related to the audio and light quality. Pretty much everything else worked. We made some basic changes, developed another version and tested that too, to come to a version – one both the users and us were happy with. We used the same process for two other training videos, where users even shot the video (though they did not edit it), and both times the results were the same. Very clearly, the users were the best creators, at least in this case.

We acted just as facilitators, and the users were creating the whole framework. It definitely helped that I knew participatory video techniques well, and it was easy for me to facilitate the process of story development and shooting.

The final training video that we shot was not participatory. Professional filmmakers, who were not related to the context at all took the script and shot the video with professional actors. This was done primarily to ensure ‘quality’ since that was the major drawback of the prototype video that we created. However, it was still ‘co-created’. After all, the script, though modified to some extent, was developed by the users.

The use of these different methods for research and prototyping gave us some strong design principles that kept us in good stead as we made several training videos over the course of 2 years. You can watch the training videos that we made on pico operation, documentation and video production here.

Do you know of designers who’ve used participatory techniques and/or processes in their design research? Have you used it yourself? I would definitely be interested to know more about your experiences in bringing together participatory videos and HCD together.

Inspiration and Ideation for Designers and Researchers

At the beginning itself, I have to admit that when I took a first glance at the human-centered design (HCD) approach, I couldn’t discern much difference between qualitative/participatory research methods and HCD research methods. I had mentioned in my earlier blog that at Digital Green, we decided to use the HCD approach to develop a more efficient training system. As we moved through the inspiration and ideation phase, I could see a lot of parallels between qualitative/participatory research and HCD, both in the approach and in the tools. However, there were some very specific differences too. What similarities did I find, and what were those differences?

Framing your Design challenge (or a Research Question)

at sorted, we set out to set ourselves a design challenge. Since creating a more effective and efficient training system was our main goal, we started developing our design challenge around it. The three main difficulties that we faced in framing our challenge were:

- How to frame a question that has appropriate scope? What is ‘nothing too wide and nothing too narrow’?

- How to ensure that our biases do not creep in into the question we frame?

- How do we know we have arrived at the right question?

These issues are very similar to those a qualitative researcher faces when developing her/his research question. One benefit of designing a challenge within an organization is that at the beginning itself you might have a very good sense of the impact that you want to have. Whereas an academic researcher is not looking at impact per se, but at the knowledge and learning that the research can help create. And, therefore, this process could be much more ambiguous for her. At the same time, working in an organizational context can limit you right at the beginning. I personally felt so caught in thoughts like, ‘But this is not how things happen at DG’, ‘But others will never be open to this’, ‘Oh, it is going to be so difficult to implement something like this.’ Before we could free ourselves to be ‘creative’ and ‘innovative’, we were binding ourselves. What helped us to get through the process was:

These issues are very similar to those a qualitative researcher faces when developing her/his research question. One benefit of designing a challenge within an organization is that at the beginning itself you might have a very good sense of the impact that you want to have. Whereas an academic researcher is not looking at impact per se, but at the knowledge and learning that the research can help create. And, therefore, this process could be much more ambiguous for her. At the same time, working in an organizational context can limit you right at the beginning. I personally felt so caught in thoughts like, ‘But this is not how things happen at DG’, ‘But others will never be open to this’, ‘Oh, it is going to be so difficult to implement something like this.’ Before we could free ourselves to be ‘creative’ and ‘innovative’, we were binding ourselves. What helped us to get through the process was:

- Not trying to resolve all problems through one question

- Coming up with lots and lots of questions, narrowing them down, deciding unanimously the one which we definitely wanted to pursue to impact our community, and then refining it.

- While refining the question, keeping the impact that we wanted to create at the center, and not letting other organizational considerations affect us at this stage.

- For the following round of refinement, keeping an eye out for the real issues at the organization and field level and tweaking the question accordingly.

When deciding our challenge, we went from very broad and ambiguous questions, for instance, ‘how can we have an efficient training system?’, to very narrow and biased ones, for instance, ‘ how can video be used to train field level workers?’. After a lot of iterations, the design challenge that we came up with, that worked for us, was ‘How might we ensure that field level workers can operate equipment confidently?’

Choosing the right methods – for generating data + creating innovative solutions

To find solutions, we started off with planning our research. It can be a tough call deciding which methods would be the most appropriate for you to find the answers and get closer to your solutions. The method that you use can determine the information and answers you get. There can be endless methods to use in HCD – you can stick to fairly traditional ones, such as interviews, to more creative ones, such as making collages, or you can even develop your own!

I felt that reaching the right methods is a comparatively well-laid down path in academic research. Once you know your research approach and the epistemology, it is easier to find suitable methods to generate data that can answer your research question. In HCD, while you know the end you want to reach, the multitude of methods and their appropriateness can be slightly tricky to navigate through. Because you do not want to simply generate data, but you want to be ‘creative’ to find an ‘innovative’ solution. There are multiple purposes that methods in HCD research must fulfill. I found that in HCD mapping the methods against three main purposes can be rather helpful. These purposes are:

- Developing some basic knowledge about the challenge

- Thinking more creatively about the actual challenges and solutions

- Learning in-depth about the challenge from the people directly facing it

We used interviews and observation extensively for our first purpose – ‘developing some basic knowledge’. Analogous inspiration helped us get some creative ideas and peer-to-peer activities helped us delve deeper into the issues that field level workers faced. For example, one of the methods that we used was to ask one field level worker to explain the functioning of the pico projector to others. The image here represents one such activity. This ‘mix-methods’ approach helped us open our minds to the various possibilities of what solutions can look like.

Prototyping solutions, iteration and messiness

We did a thematic data analysis right after our secondary research and interviews to get further direction, and developed‘sub-challenges’ or ‘insight statements’. We zeroed in on three main things that can be possible solutions for an effective training system: 1) contextual training videos; 2) game-based objective assessment; 3) illustrative handout.

So far so good. So far very much like academic research. But this is where things changed… and got messy. Collecting data, analyzing it, developing prototypes, testing prototypes, collecting more data, analyzing the new data, developing another prototype…. All of it went on in a very intuitive and non-linear manner. One day you conduct a peer-to-peer activity and the very next day you’ve done a quick analysis developed a prototype and are out in the field testing it. It was nothing like… a literature review of data collection to data analysis to writing… what I did in a step-by-step manner while doing academic research. And the messiness didn’t make someone like me, who does things very systematically, happy and comfortable!

The messiness of the process also created some friction in the team, because often things didn’t make a lot of sense and I, for one, questioned if it was leading anywhere. But the deeper we dug, answers started becoming clearer. The more iteration we did on prototypes, the closer we got to our solution. After all, like they say, there was some method to the madness. What I learnt was this:

- Do not rely too much on assumptions based on your thematic analysis. Rely more on what the real life scenarios teach you.

- Prototyping can feel difficult, but just make something! Even a really quick and bare prototype will give you insights

- Every iteration should bring something new and answer your design challenge. When that stops happening, stop prototyping.

The hidden academic researcher in me initially desisted the quick iterative and non-linear nature of HCD, but also realized that the value in it is you do not spend too much time creating a ‘beautiful’ solution, which doesn’t work all that well. Quick iterations help you get rid of bad ideas before you’ve put in too much effort, money and time, and (more dangerously) before you get quite convinced about your ideas yourself!

More than the ‘method’, the madness was what I started enjoying in our subsequent use of HCD. This included creating our own ‘methods’ and process variations. Since I have done participatory video, I used some techniques from it for developing prototypes. In my next blog, I would focus on using participatory video technique in HCD, what it meant for us to co-create and where it took us while creating our solutions.