The fall armyworm (FAW), Spodoptera frugiperda, was first reported on the African continent in early 2016 and, in Ethiopia alone, has infested approximately a quarter of the 2.6 million hectares of land planted with maize since 2017. To tackle the devastation, the Government of Ethiopia set up a National Technical Advisory Committee on FAW (FAW TAC) in early 2018 which includes government stakeholders such as the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Resources (MoALR) and the National Agricultural Research Council (NARC); agriculture universities, donors such as FAO and USAID; and implementing partners such as Digital Green and Fintrac. The FAW TAC is faced with a challenging mission. Given the extent of devastation that FAW has already wrought on smallholder maize farmers in Ethiopia, one tool or strategy to survey, monitor, report and combat the pest will not be enough. To tackle the national spread, an effective solution will require a menu of options and a multi-pronged approach.

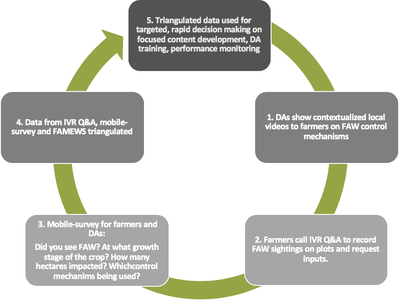

The Feed the Future Developing Local Extension Capacity project (DLEC) is piloting a multi-channel, multi-stakeholder approach leveraging video-enabled extension, a national IVR question and answer (Q&A) forum, a mobile-based farmer and extension agent survey, and the Fall Armyworm Monitoring and Early Warning System (FAMEWS) – a mobile application deployed by the MoALR and FAO. We hypothesize that the systematic integration of these channels can create a demand-driven, timely and responsive pest management system.

DLEC is implementing the pilot in collaboration with the Feed the Future Ethiopia Value Chain Activity (FTF-EVCA) implemented by Fintrac in ten woredas in Amhara and Oromia regions of Ethiopia and will include 25,000 farmers. The outcome we are seeking is to leverage existing national systems and partnerships with ongoing projects to create a holistic digital suite of tools and collect real-time data to enable rapid, targeted decisions about how to develop focused and contextual content, train extension agents and farmers and monitor performance to combat the spread of FAW.

The diagram above shows the multi-pronged approach that involves government extension agents showing local videos on FAW scouting and control mechanisms, farmers calling the IVR Q&A line to record FAW sightings, government and partners conducting a mobile survey for additional real-time data, and the FAW TAC and others using the multiple data sources for effective and efficient decision-making on FAW mitigation. One of the roles that DLEC plays is to ensure that the FAW control practices shown in the videos can actually be implemented by the farmers. The videos also promote good agricultural practices to get high nutrients and reduced pests in maize plants such as tillage after harvesting for soil polarization, timely planting, intercropping and push-pull cropping; local practices such as broadcasting of ash, sand, pepper and soap into infested whorls; and organized system-related activities such as parasitoid and pathogen verification and registration.

Our hope is that this multi-pronged integrated approach can help farmers combat FAW, and the lessons learned can be leveraged to fight other pests and diseases as well. We’ve just begun implementation so watch this space for updates, results and lessons learned. And do share what you’re learning in pest management and integration of digital tools and messages to enable real-time decision making.