The 9th of every month is a significant day for Digital Green as is the case for thousands of pregnant women in India since the launch of the Pradhan Mantri Surakshit Matritva Abhiyan (PMSMA) on June 9, 2016.

With a vision of providing quality maternal care services to the women in our country, Ministry of Health & Family Welfare (MoHFW), Government of India launched the PMSMA in 2016 which aims to provide assured, comprehensive and quality antenatal care (ANC), free of cost, universally to all pregnant women on the 9th of every month to ensure that every pregnant woman receives at least one check-up in the 2nd or 3rd trimester of pregnancy by a doctor at the designated health facility. On this day, the pregnant women can also get all the relevant tests along with ultrasonography to ensure safe pregnancy and tackle any high-risk situation.

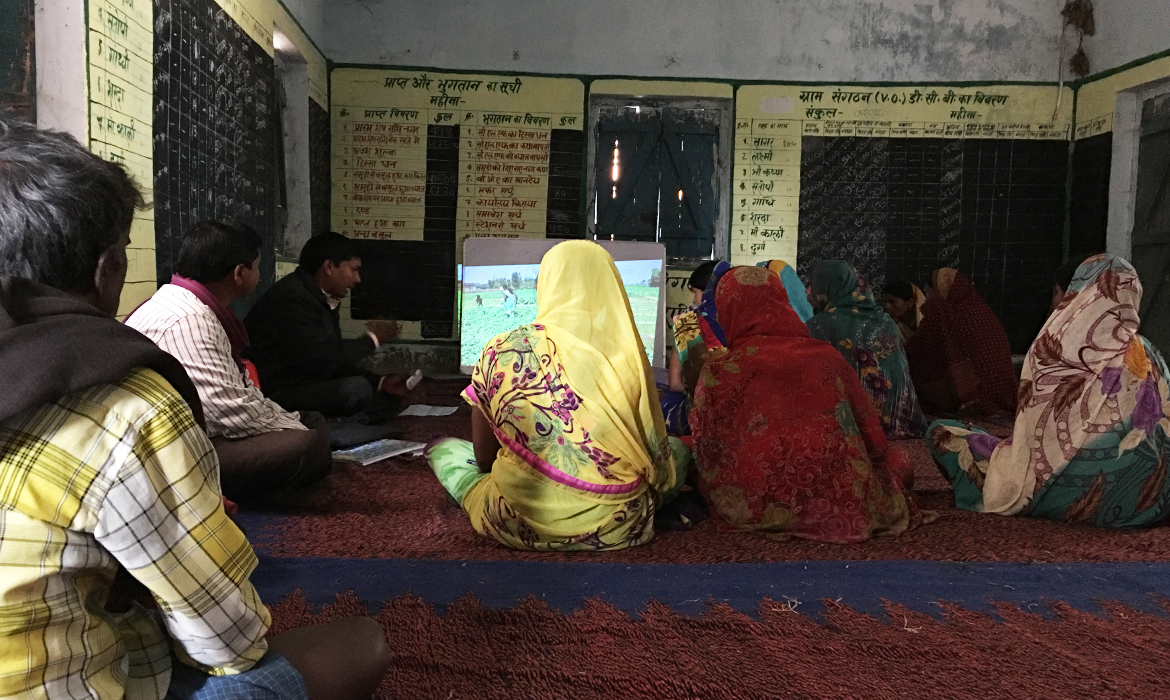

The PMSMA events witness a huge footfall of pregnant women who want to avail the comprehensive ANC, which also leads to a long‘waiting’period. We wanted to take advantage of this time to disseminate community videos among pregnant women from the rural communities. For instance, on the 9th of May 2018 nearly 270 pregnant women of Parbatta block, Khagaria district reached the PHC for their ANC during which our team was able to disseminate the videos on ‘Importance of IFA tablets’ and ‘diet diversity during pregnancy’.

Under our USAID-funded project Samvad, we aim to improve family planning, maternal child health and nutritional outcomes in 6 states of India, namely, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Odisha, Uttarakhand and Assam. (Read more about the project here.) In Bihar, we had been leveraging our existing partnership with JEEViKA to reach a broader audience that would include not only our primary target beneficiaries (pregnant and lactating women) but also the influencers as well through self-help groups (SHGs) or Voluntary Organizations (VOs).

However, we realised that we would need to target our audiences more effectively to optimally reach the beneficiaries. With that objective, we started exploring various ways of reaching our target audiences in a more deliberate manner through the Anganwadi centres on Village Health Sanitation and Nutrition Days (VHSNDs) – another interesting initiative by the Government of India – focusing on improving maternal and child health and nutrition.

Further, we had an opportunity to discuss our project with Dr Dinesh Baswal, Deputy Commissioner, Maternal Health, MoHFW who first mentioned the window of opportunity – the waiting period at the PMSAMA day – for the dissemination of our localised videos. Further discussions with Dr Phuleshwar Jha, State Program Manager – Maternal Health, State Health Society, Bihar Govt., opened up the possibility of engaging with the community through the platform of PMSMA. We received enormous encouragement from him and his team in Nalanda, Saharsa and Khagaria as well as that of the Health and Nutrition Manager, JEEViKA at the districts and also other partner organizations such as Project Concern International who helped us build upon their existing relationships with the staff of hospitals where these camps are often held.

At the PHC centre at Parbatta block of Khagaria, I was very impressed by the entire process and attention to d etail that marked the success of the program. There were pick and drop facility by the 108-ambulance provided to pregnant women coming from distant places; the pregnant women were accompanied by an ANM/ASHA for the PMSMA day; at the health facility, the process was made smoother by having two counters each for registration and collection of blood samples; an ANM played a pivotal role by collecting the vital information about the pregnant women and providing counselling around the do’s and don’ts during pregnancy.

etail that marked the success of the program. There were pick and drop facility by the 108-ambulance provided to pregnant women coming from distant places; the pregnant women were accompanied by an ANM/ASHA for the PMSMA day; at the health facility, the process was made smoother by having two counters each for registration and collection of blood samples; an ANM played a pivotal role by collecting the vital information about the pregnant women and providing counselling around the do’s and don’ts during pregnancy.

For us, this was great opportunity to disseminate our videos while the pregnant women and their family members were waiting for their pathology reports and follow up consultations with the doctors. The ANMs and ASHA workers helped us gather pregnant women in a hall within the hospital premises where the video dissemination was conducted in groups of 50 at a time. This occasion was also used to explain the importance of nutrition, family planning, institutional delivery and breastfeeding up to the age of six months by the ANM.

After the video dissemination, we gathered feedback from the pregnant women and their family members about the videos and they found the videos to be very engaging and informative. They also felt the practices shared were easy to adopt and requested dissemination of such videos in their villages in future.

The opportunity to connect directly with this group of pregnant women within such a controlled environment with life stage-specific targeted messages – I am hopeful – will truly bring about the behaviour change we are aiming for.

hain have injected an entrepreneurial mindset in the rural women which can be harnessed to develop enterprise models. It is so energizing to see rural women making videos or disseminating them, holding discussions on the pros and cons of various practices. Apart from promoting good practices, this approach has resulted in empowering them in a variety of ways. I have been personally struck by their self-confidence every time I have watched a video dissemination in a village or interacted with them.

hain have injected an entrepreneurial mindset in the rural women which can be harnessed to develop enterprise models. It is so energizing to see rural women making videos or disseminating them, holding discussions on the pros and cons of various practices. Apart from promoting good practices, this approach has resulted in empowering them in a variety of ways. I have been personally struck by their self-confidence every time I have watched a video dissemination in a village or interacted with them.

local tribal women. I asked how many of them fed their baby breast milk within the first hour of the birth. I was surprised that most of the women raised their hand. Upon further probing, they related this practice to how the calf is fed its mother’s milk immediately after birth. This simple parallel that they drew with nature around them displayed such wealth of knowledge that I felt ashamed to have doubted their apparent simplicity.

local tribal women. I asked how many of them fed their baby breast milk within the first hour of the birth. I was surprised that most of the women raised their hand. Upon further probing, they related this practice to how the calf is fed its mother’s milk immediately after birth. This simple parallel that they drew with nature around them displayed such wealth of knowledge that I felt ashamed to have doubted their apparent simplicity.

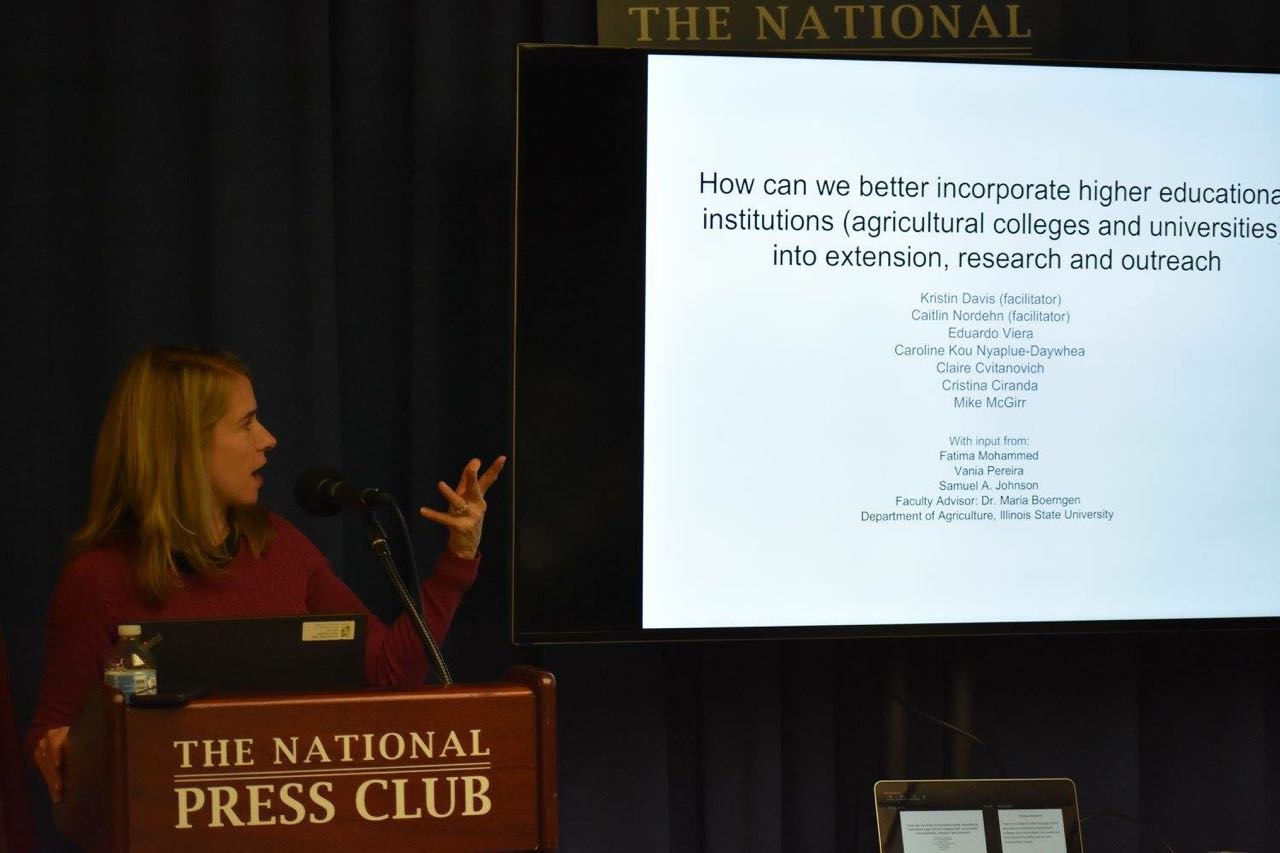

While there is a renewed emphasis on extension in many countries, there are persistent challenges that remain. We still are not reaching women farmers in the numbers we should, there are issues with adequate transportation and infrastructure, extension workers lack training in information and communication technologies and many work in isolation from other key extension providers. When daily facing these problems, the challenges can seem daunting, but they don’t have to be if we face them together.

While there is a renewed emphasis on extension in many countries, there are persistent challenges that remain. We still are not reaching women farmers in the numbers we should, there are issues with adequate transportation and infrastructure, extension workers lack training in information and communication technologies and many work in isolation from other key extension providers. When daily facing these problems, the challenges can seem daunting, but they don’t have to be if we face them together. Our participants were key agricultural development stakeholders from governments, donors, researchers and private and civil society practitioners. They came from Bangladesh, India, Liberia, Kenya, Uganda and USA. In addition, we conducted video interviews with extension workers from several countries to ensure we had

Our participants were key agricultural development stakeholders from governments, donors, researchers and private and civil society practitioners. They came from Bangladesh, India, Liberia, Kenya, Uganda and USA. In addition, we conducted video interviews with extension workers from several countries to ensure we had

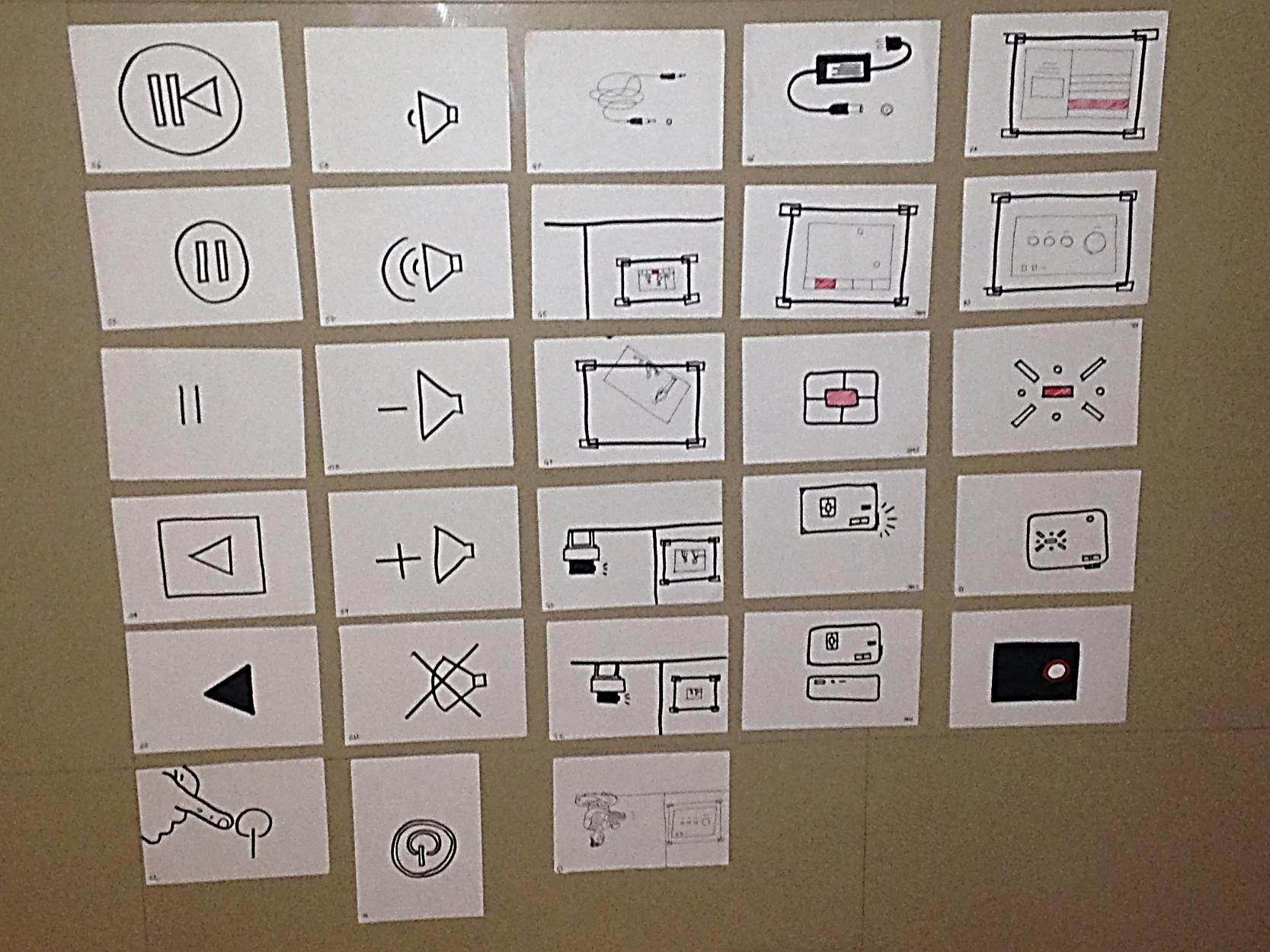

These issues are very similar to those a qualitative researcher faces when developing her/his research question. One benefit of designing a challenge within an organization is that at the beginning itself you might have a very good sense of the impact that you want to have. Whereas an academic researcher is not looking at impact per se, but at the knowledge and learning that the research can help create. And, therefore, this process could be much more ambiguous for her. At the same time, working in an organizational context can limit you right at the beginning. I personally felt so caught in thoughts like, ‘But this is not how things happen at DG’, ‘But others will never be open to this’, ‘Oh, it is going to be so difficult to implement something like this.’ Before we could free ourselves to be ‘creative’ and ‘innovative’, we were binding ourselves. What helped us to get through the process was:

These issues are very similar to those a qualitative researcher faces when developing her/his research question. One benefit of designing a challenge within an organization is that at the beginning itself you might have a very good sense of the impact that you want to have. Whereas an academic researcher is not looking at impact per se, but at the knowledge and learning that the research can help create. And, therefore, this process could be much more ambiguous for her. At the same time, working in an organizational context can limit you right at the beginning. I personally felt so caught in thoughts like, ‘But this is not how things happen at DG’, ‘But others will never be open to this’, ‘Oh, it is going to be so difficult to implement something like this.’ Before we could free ourselves to be ‘creative’ and ‘innovative’, we were binding ourselves. What helped us to get through the process was:

At that time the price of the crop increases from INR 10 per kg to about INR 100 per kg, making it quite lucrative for farmers. The price, of course, depends on the market, and the key to realizing a good profit is information on the rates in different markets – and this is exactly what the LOOP app facilitates. I learned that before being part of the LOOP project, farmers normally went to the Pune flower market where they got a rate of about INR 45 – 50 per kg during peak season. This is almost half of their INR 80 per kilo earning from a four-day sale of flowers in Mumbai through LOOP. With an additional net profit of INR 350,000 from the sale, farmers were more than thrilled to be a part of the program. In fact, one among those farmers chose not sell his flowers with the others, and realized a price of INR 45 per kg only, losing out on the additional profit. From this experience, now these farmers are tapping markets for other crops they grow. Recently, they made a sale of inferior quality raw bananas in one of Mumbai’s chips making value chain, instead of the Panghat market where they usually went.

At that time the price of the crop increases from INR 10 per kg to about INR 100 per kg, making it quite lucrative for farmers. The price, of course, depends on the market, and the key to realizing a good profit is information on the rates in different markets – and this is exactly what the LOOP app facilitates. I learned that before being part of the LOOP project, farmers normally went to the Pune flower market where they got a rate of about INR 45 – 50 per kg during peak season. This is almost half of their INR 80 per kilo earning from a four-day sale of flowers in Mumbai through LOOP. With an additional net profit of INR 350,000 from the sale, farmers were more than thrilled to be a part of the program. In fact, one among those farmers chose not sell his flowers with the others, and realized a price of INR 45 per kg only, losing out on the additional profit. From this experience, now these farmers are tapping markets for other crops they grow. Recently, they made a sale of inferior quality raw bananas in one of Mumbai’s chips making value chain, instead of the Panghat market where they usually went.

Another farmer M.V. Subba Rao from East Godavari district has been looking for literature and relevant information on zero-budget natural farming and pointed out that Digital Green extension system will be helpful to farmers in his community. Gundra Ambayya, a smallholder farmer from V.Kothapalli village in East Godavari district requested that we transfer the videos on natural farming methods onto his mobile phone – which we did with pleasure. While watching a video on natural farming method for cultivating tomatoes, one farmer asked us “Why did they put a stick as a support for the tomato plant?” He wanted to watch more such videos on vegetable cultivation. Many Agriculture Sciences students were also fascinated by the videos and agreed that it’s a good way to reach many farmers.

Another farmer M.V. Subba Rao from East Godavari district has been looking for literature and relevant information on zero-budget natural farming and pointed out that Digital Green extension system will be helpful to farmers in his community. Gundra Ambayya, a smallholder farmer from V.Kothapalli village in East Godavari district requested that we transfer the videos on natural farming methods onto his mobile phone – which we did with pleasure. While watching a video on natural farming method for cultivating tomatoes, one farmer asked us “Why did they put a stick as a support for the tomato plant?” He wanted to watch more such videos on vegetable cultivation. Many Agriculture Sciences students were also fascinated by the videos and agreed that it’s a good way to reach many farmers.