The first time that I heard the term ‘human-centered design’, was when I was doing my PhD and felt that it was another one of those buzzwords – what is being done is simplistic, but is made to sound complex. I did not know then that I would end up using it extensively at my work with Digital Green, and quite successfully too. What has encouraged me to write this series of blog on HCD is that I have used it for over 2 years in my work, which has given me enough time to reflect and make my own meaning of the process. Through these blogs, I capture some of that journey.

Scaling-up and HCD at Digital Green

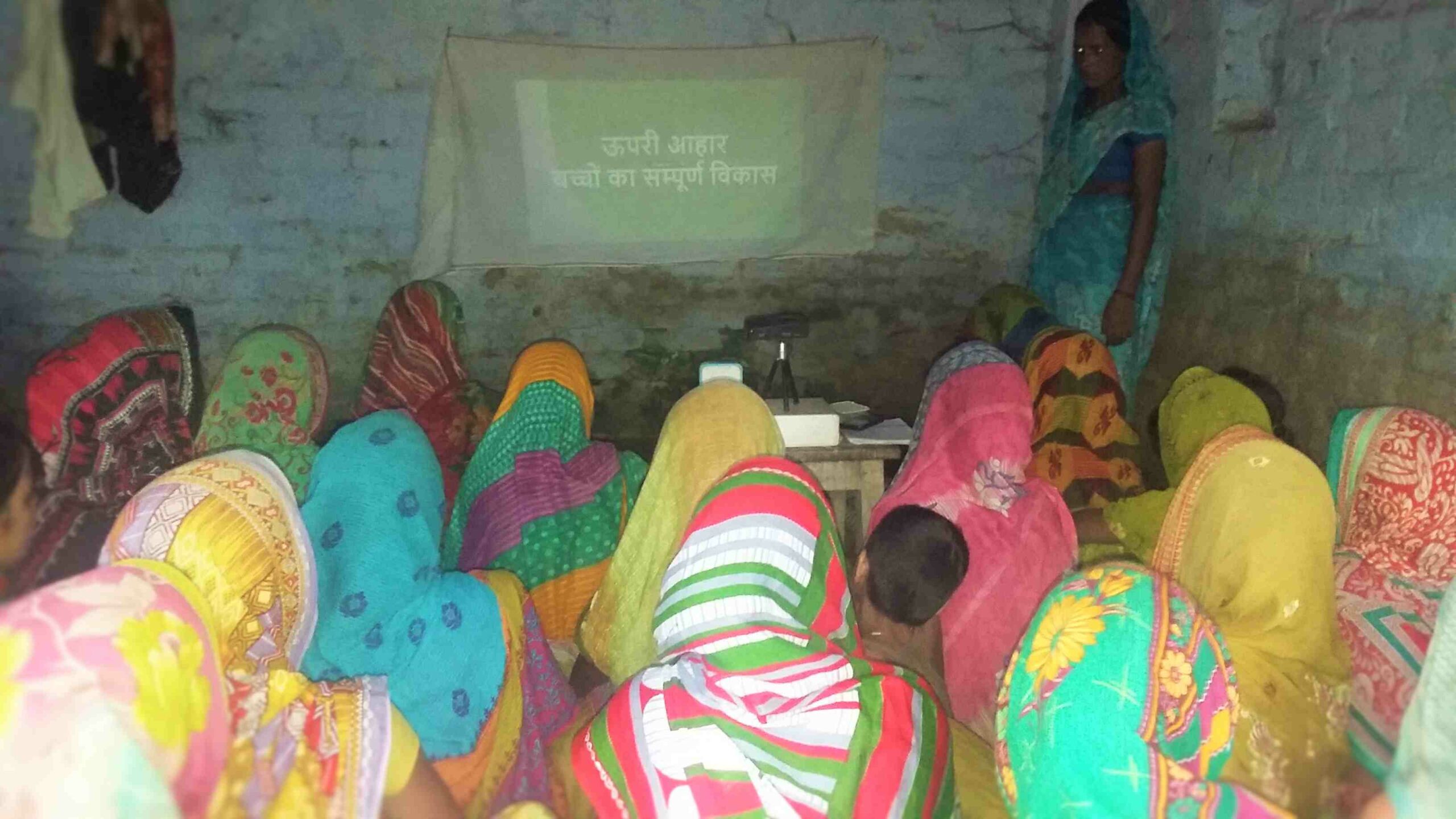

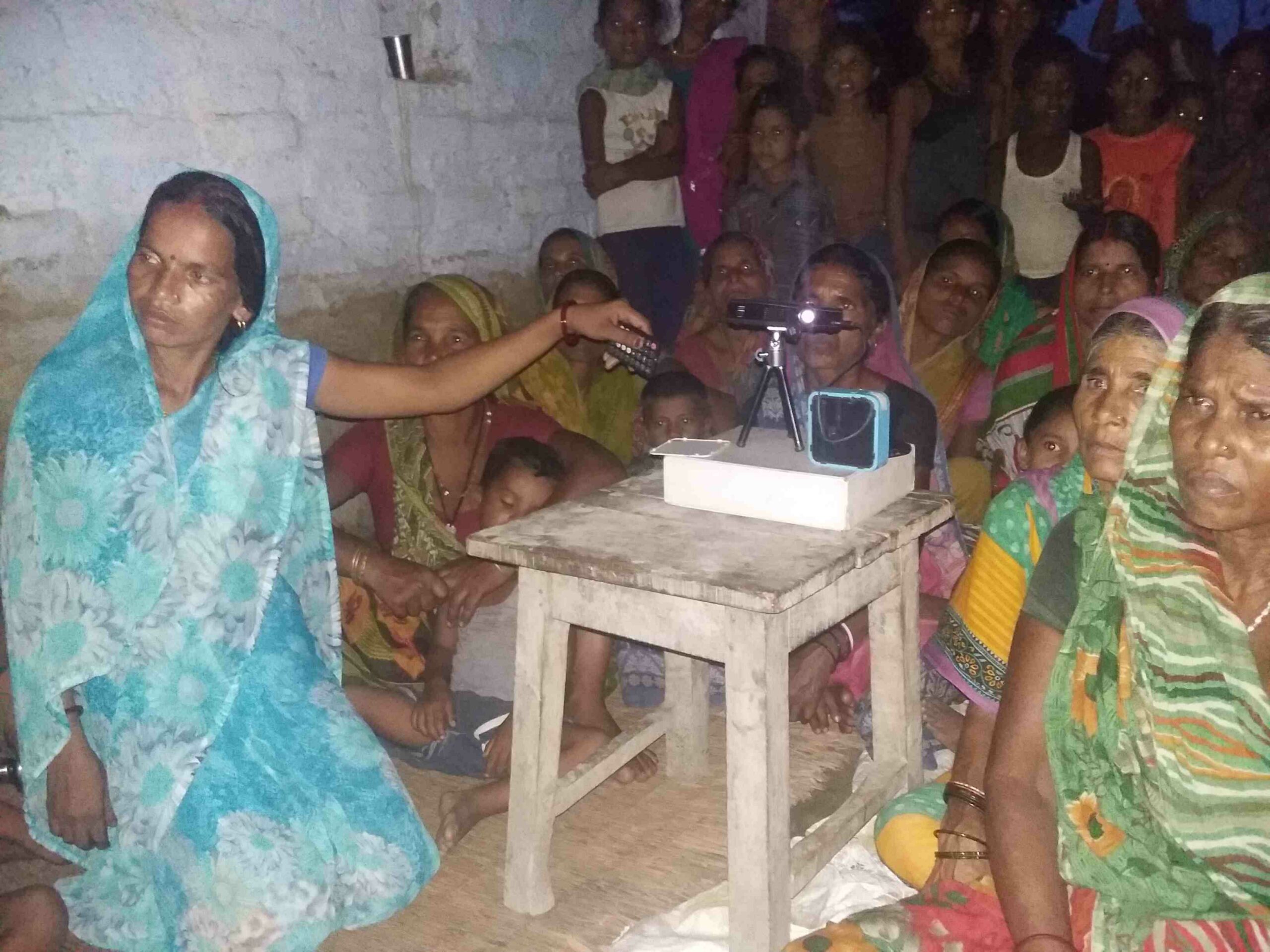

At Digital Green, a lot of work is centred on developing pieces of training for field-level workers in producing localized videos on agriculture, health and nutrition, and showing those to rural communities. The videos are shown in small groups using a battery-operated pico projector and facilitated by field-level workers. As we scaled, our concern, similar to several organizations’, was maintaining the quality of our training. As we hire more and more trainers, how do we make sure that all of them are training field-level workers effectively? As trainers give more and more training, how do we know what field-level workers are actually learning to an optimal level?

We were looking to develop an innovative training system, where there was some amount of standardization, assurance of quality and learning for the ‘users’ – the field level workers. Several ideas were discussed, pilot projects proposed, strategy documents were written, ‘trial’ training videos made…but somehow things were not moving, and they did not seem quite right. We soon found that there was little space for iterations because there was a confidence that what we are proposing after brainstorming in our office conference room, is going to work with the field-level workers. Thankfully, we decided to change our approach.

Notes from brainstorming sessions

What worked for us to get it off the ground

I am a participatory researcher, and when my colleague introduced me to IDEO’s human-centered design approach, it immediately clicked. We extensively used their field guide to help us design our training system. But before I get to how we used it and what came out of it, I want to talk about how we even got started with using it.

One of the biggest questions about some methods, tools and techniques is that if they have been proven to work, then why are more and more people not adopting it? The answer is often the obvious one – it simply does not suit their context and environment. Similarly, every non-profit and its systems might not lend themselves to successfully using HCD, howsoever much they believe in its impact. In our case, it worked for us. The reason for it was a mix of two main ingredients: Attitude and Resources.

ATTITUDE

- Being open to change. Innovation is the cornerstone of HCD. Even if you are “participatory” in your regular work, but not open to creating something completely different, HCD might not work at all. It is an uncomfortable position. We all tend to get used to our regular ways of working (even if they are inefficient or not as effective). In organizations, even a small and simple-looking change might require changing hard-set systems and processes. If an organization is intrigued to try it and make it successful, it has to be open to changes at several levels. Innovation cannot happen in isolation. Being open to change was what helped us wade through the murky waters of innovation.

- Being quick to change and iterate. You cannot want to be innovative and yet be bureaucratic in your way of working. The two just do not support each other. Non-profits can sometimes be more bureaucratic than government agencies, members can pick apart issues more than seasoned academicians, and decisions might never be taken, agreements never reached. At DG, we kept a pretty small team, which was able to work independently, throw away bad ideas, create iterations of prototypes and move on. We committed ourselves to be open to what we learn, and change as we need. This wasn’t without serious arguments on viewpoints of different team members though! It’s funny how quickly we start loving our ideas, and feel such a pain when we figure that it not working. But things which are not working… throw away we must!

RESOURCES

- Tenacity to keep trying even after failing several times. Though this might sound like an attitude, it is not just about having a belief in innovation and keeping an open mindset. It is also to do with funding. How many non-profits have funding that allows them to try and fail? Then try again and fail? It is such an oft-discussed topic that I can probably add nothing new. But, after all, with project targets always chasing you, how many times can you fail? We, luckily, had an empathetic donor, who was happy for us to innovate, who wasn’t asking us why we were failing, but rather what we failed at and how we addressed it. I doubt that without such support, we could have tried being innovative.

- Right human resources. Now, I am not a trained human-centered designer. But I am trained in qualitative and participatory research. Our team also consisted of people who had done IDEO’s online course and we had required subject experts. I am not entirely sure how successful it would have been with an internal team which just tried to follow the guide. There is a lot of stuff written by scholars and practitioners on how participatory methods and training can be treated by researchers/trainers as a technical process and not an empowering approach. The same can hold true for HCD as well. The IDEO.org’s guide does focus a lot on ‘Mindsets’, before it gets down to ‘Methods’, presumably to help people not fall into that same trap. It also suggests building an interdisciplinary team. But, like funding, several non-profits suffer from a lack of good trained human resource. For us, getting the right people together helped like nothing else – a team which knows which are the right methods in which situation, to get to a workable solution.

With these four main things in place, we started on our HCD research. What are the things that worked for you and your team? What do you think about settings and contexts that support HCD?

s organic pesticide on all his crops. He also continues to attend the video screenings to learn new methods.

s organic pesticide on all his crops. He also continues to attend the video screenings to learn new methods.