“It’s the end of the world,” said the caterpillar!

“It’s just the beginning of the world,” said the butterfly!

– Author Unknown

I have seen that butterfly’s optimism in a farmer from a small village, Nandivelugu of Guntur district, Andhra Pradesh, India and it reaffirms my belief in the promise of natural farming and our farmers’ spirit and resilience!

There are many worlds within our world; for 30-year-old Arisetti Naga Malleshwari her world is 60 cents (0.6 acre) of her family-owned land and an additional 20 cents (0.2 acre) that is rented. Natural farming has made a world of difference to her small world.

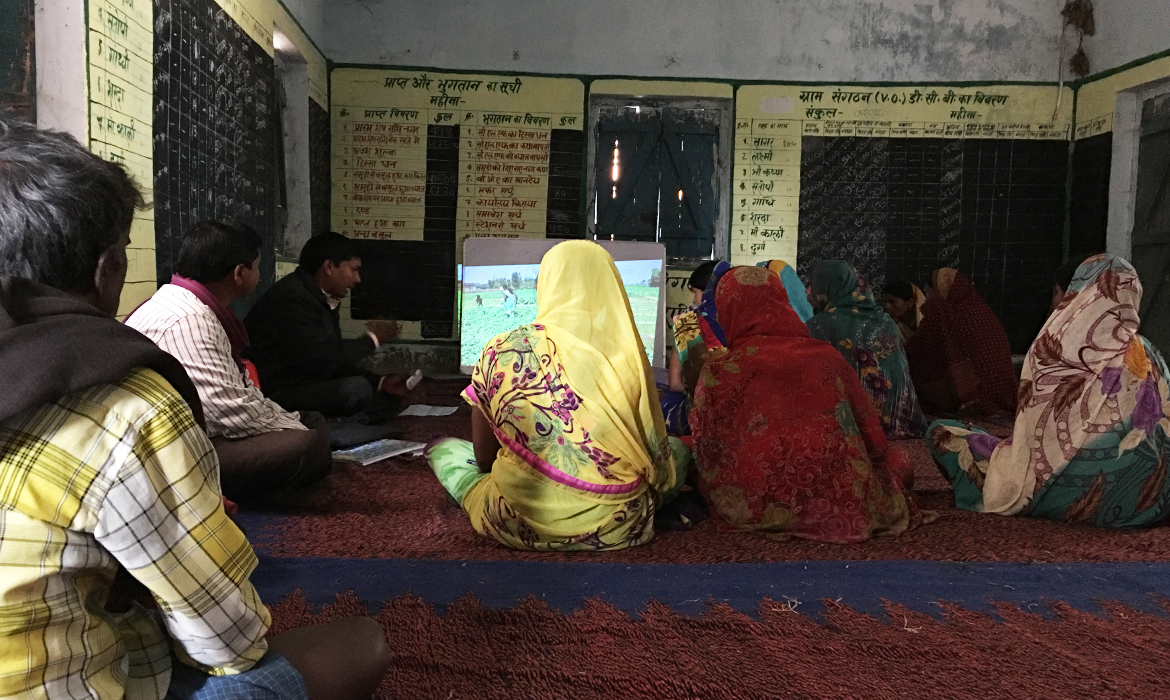

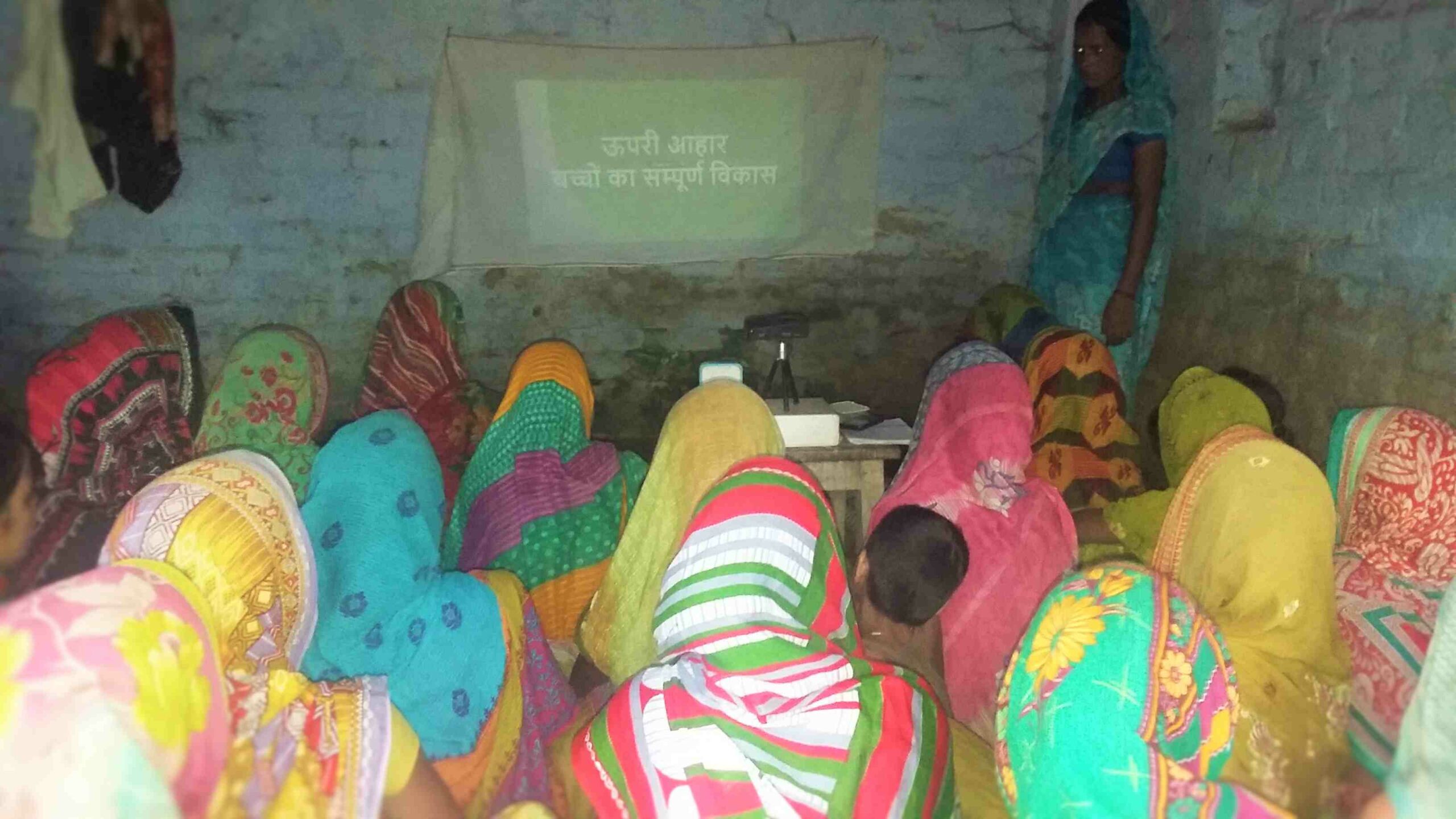

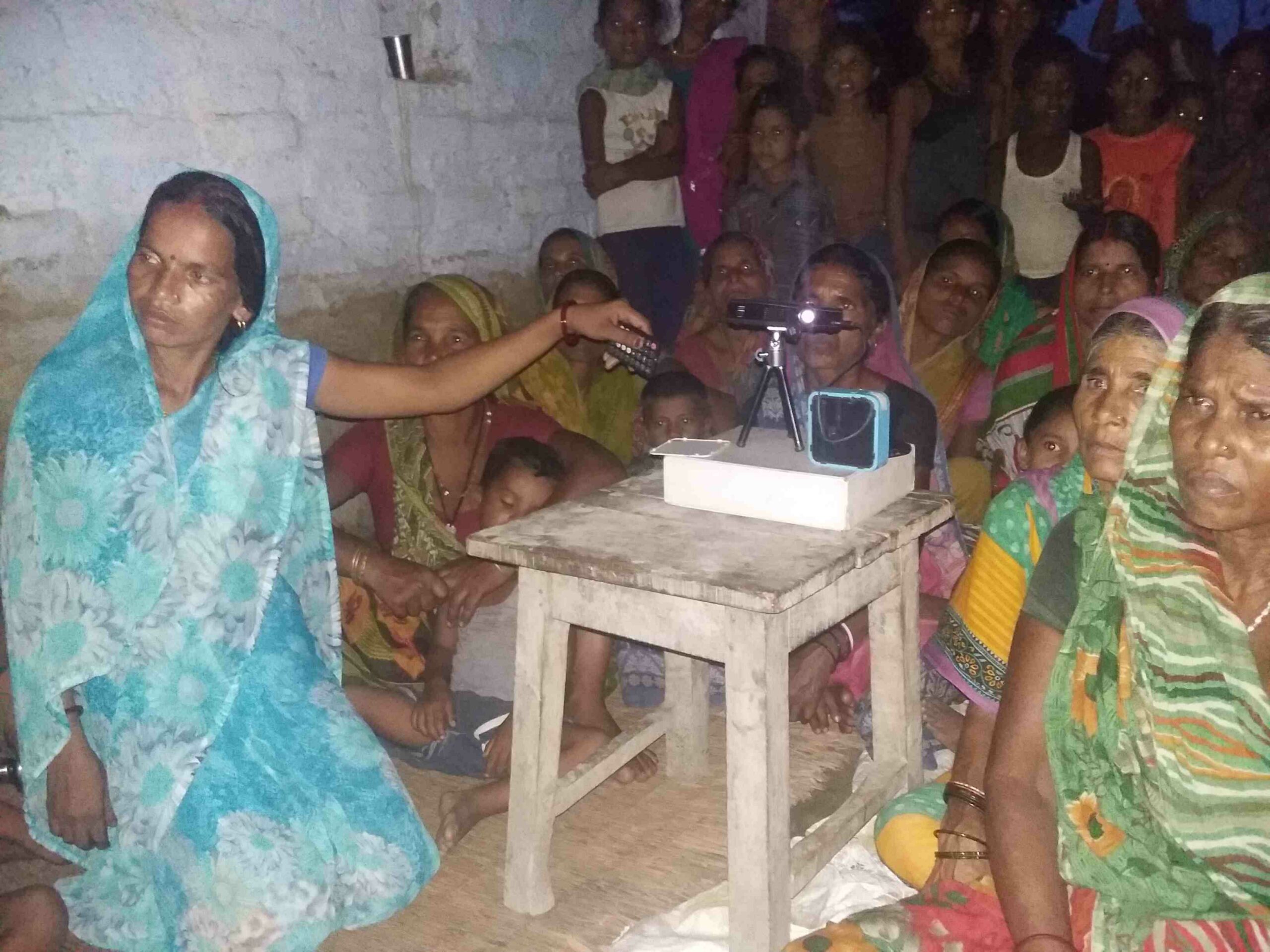

Mired in chronic debt over ten years of conventional farming, Naga Malleshswari and her husband Panduranga Rao decided to change the way they practised agriculture and adopted zero-budget natural farming(ZBNF) in the Kharif season of 2017. Inspired by her father, Chandu Sambasiva Rao who is growing five varieties of paddy landrace (native varieties) in Aathota village on a meagre 20 cents of rented land. He did this with support from the Andhra Pradesh Department of Agriculture and Cooperation (DoAC) & Rythu Saadhikaara Samstha (RySS)’s cluster activist, Ms Parishudda Kumari. After learning science and practices of natural farming by watching Digital Green community videos, Naga Malleshwari practised all important natural farming practices in Paddy, Jowar, and Colocasia.

Initially, Naga Malleshwari was filled with doubt due to the ridicule from her fellow farmers. But when she had harvested 18 bags of paddy from the 60 cents of land in November 2018, all her fellow farmers were convinced. The cost of cultivation in conventional farming (approx.. Rs. 10,000) was reduced (to Rs.4,000) in natural farming. Application of natural fertilizers and pesticides not only yielded a bumper crop, but it also ensured quality and healthy growth of crops. “I am yet to sell the paddy but the buyers are offering Rs.2,000 per bag; a profit of Rs. 200-400 per bag of the conventionally grown crop,” she shared with pride.

After harvesting paddy, she sprayed cow dung-cow urine-asafoetida extract on the empty land as a precautionary practice to eliminate any residual fungi before planting Jowar (sorghum) in the Rabi season. She followed all ZBNF practices for the Rabi crop as well. Seed treatment with Beejamrutam, Ghanajeevamrutham application, spraying of Dravajeevamrutham and neem seed kernel extract and installed pheromone traps to monitor pests.

She shared that conventional methods of farming Jowar involve heavy usage of urea which results in higher levels of plant and weed growth during the grain formation stage, in turn resulting in lower yields. She is expecting higher yields and higher prices from the Jowar crop this time – (nearly 15 quintals that may fetch Rs.15,000) while the cost of cultivation was approx. Rs.1,000. On the 20-cents of rented land, Naga Malleshwari cultivated Colocasia using the ZBNF practices. Now, with reduced cultivation costs and higher yields, her net income was Rs.14,000, which is more than double the Rs.5,000 – 7,000 she used to receive.

“We have been debt-free since last two years,” shared Naga Malleshwari. “I am also growing several types of vegetables in my kitchen garden using the ZBNF method, which is sufficient for household consumption.” “I grew broad beans on paddy bunds during the last season,” she added. She was conscious of the health and nutrition benefits of consuming natural farming produce for her family of five members.

When almost all curry-leaf plants in her neighbourhood were affected with powdery mildew disease last summer she convinced all her neighbours to spray sour buttermilk on the plants – the practice was effective, and this marked Naga Malleshwari’s first step in spreading ZBNF practices among her fellow farmers. As a Community Resource Person (CRP), she supported many paddy farmers in her village in the adoption and practice of natural farming in the Kharif season of 2018.

“I have attended several video disseminations on ZBNF and I interact regularly with resource persons to further build my understanding of natural farming,” she shared.

Change is slowly coming full circle in Naga Malleshwari’s natural farming journey. She began as a farmer merely practising natural farming, and is now playing a leadership role in supporting and encouraging her fellow farmers to adopt and practice natural farming. I am sure that Naga Malleshwari will continue to create many more circles of inspiration in her farming community!

“I have been farming for the last 60 years. But it’s the first time in my life that my 2-acre paddy field yielded grains sufficient for my whole family to last three years. This is after I sold half of the yield,” shared 75-year old farmer Pattika Parsaiah whose farm depends on the rains. The conventional method of cultivation would yield 18-20 bags per acre (a bag is 50 kgs) that is 9-10 quintals. Last year after adopting SRI in the natural farming method, it yielded 40 bags (20 quintals).

“I have been farming for the last 60 years. But it’s the first time in my life that my 2-acre paddy field yielded grains sufficient for my whole family to last three years. This is after I sold half of the yield,” shared 75-year old farmer Pattika Parsaiah whose farm depends on the rains. The conventional method of cultivation would yield 18-20 bags per acre (a bag is 50 kgs) that is 9-10 quintals. Last year after adopting SRI in the natural farming method, it yielded 40 bags (20 quintals). tremendous joy. All the learning, sharing, video screenings, trainings, farmer-field schools, have borne fruits – the increased yields and farmers’ incomes… our village becoming the first 100% natural farming village in our state. All these fill us with great excitement… Our village feels like one family… Our people have proved it…” shares the village head, Thuyuka Manjuvani.

tremendous joy. All the learning, sharing, video screenings, trainings, farmer-field schools, have borne fruits – the increased yields and farmers’ incomes… our village becoming the first 100% natural farming village in our state. All these fill us with great excitement… Our village feels like one family… Our people have proved it…” shares the village head, Thuyuka Manjuvani.