Roundtable Dialogue on Innovations and Lessons on what works to empower women farmers.

29th March 2023 | New Delhi, India

What works to empower women farmers? What are the methodologies, innovations, strategies that have worked to empower them? What are the lessons and challenges encountered in the pathway to enable women farmers to become agents of their own transformative change? Driven by these questions, in March 2023, Digital Green organized a roundtable dialogue in New Delhi; a day of deliberations with experts and development professionals from organizations that engage with women farmers. The dialogue was anchored around deconstructing ‘empowerment’ alongwith strategies, framework and pathways that various organizations have been using to empower women farmers. Additionally a session was dedicated to the discussion on digital innovations used by the participating organizations to empower women collectives.

The dialogue, organized into three thematic sessions, began with context setting by Krishnan Pallassana (Managing Director, Digital Green) with chief address by Mr. Chiranjit Singh, IFoS, Additional Secretary at the Ministry o f Rural Development. Krishnan Pallassana in his welcome note emphasized on the primacy of women farmers in the agricultural ecosystem – who are responsible for ensuring employment, food and nutrition security. While Mr. Chiranjit Singh highlighted the need to contextualize and tailor solutions to build capacities of rural women; striving for innovative solutions with an intersectional lens to harness the power of social media and digital technologies to boost capacity building at scale. The speaker foregrounded the need for collaboration and convergence among ecosystem players, expressing that “the government is keen to explore and utilize the power of digital technologies to empower women farmers through the expansive network of community resource people and grassroots infrastructure.” The session concluded with a screening of a short film of women farmers (that Digital Green has been working with) elaborating on what empowerment meant for them.

f Rural Development. Krishnan Pallassana in his welcome note emphasized on the primacy of women farmers in the agricultural ecosystem – who are responsible for ensuring employment, food and nutrition security. While Mr. Chiranjit Singh highlighted the need to contextualize and tailor solutions to build capacities of rural women; striving for innovative solutions with an intersectional lens to harness the power of social media and digital technologies to boost capacity building at scale. The speaker foregrounded the need for collaboration and convergence among ecosystem players, expressing that “the government is keen to explore and utilize the power of digital technologies to empower women farmers through the expansive network of community resource people and grassroots infrastructure.” The session concluded with a screening of a short film of women farmers (that Digital Green has been working with) elaborating on what empowerment meant for them.

With this, the first round of deliberations were rooted in examining ‘empowerment’ from the lens of women farmers’ lived experiences. The participants explored the fluidity of the term itself and the difficulty to capture the subjective experience of being empowered. The participants underlined that women’s identities are relational and contextual, thus they should not be perceived as homogenous entities. Interventions for empowerment need to be designed to challenge gender inequities and power asymmetries, by facilitating conducive conditions for women to be able to challenge systems and structures to ensure they can thrive in both public and private spaces. With a concept as fuzzy as empowerment, the participants agreed that it presented its own set of challenges when it came to evaluation or measuring it. Thus a lot of interventions and efforts oscillate between economic development and economic empowerment.

With this, the first round of deliberations were rooted in examining ‘empowerment’ from the lens of women farmers’ lived experiences. The participants explored the fluidity of the term itself and the difficulty to capture the subjective experience of being empowered. The participants underlined that women’s identities are relational and contextual, thus they should not be perceived as homogenous entities. Interventions for empowerment need to be designed to challenge gender inequities and power asymmetries, by facilitating conducive conditions for women to be able to challenge systems and structures to ensure they can thrive in both public and private spaces. With a concept as fuzzy as empowerment, the participants agreed that it presented its own set of challenges when it came to evaluation or measuring it. Thus a lot of interventions and efforts oscillate between economic development and economic empowerment.

Another participant highlighted that empowerment, like the woman herself, is a composite of different elements, including identity, agency, autonomy, and literacy, that are critical elements in the pathway to empowerment. The discussants associated choice, negotiation, and decision-making intrinsically with empowerment. The floor agreed that empowerment could mean differently for different women – for some women taking up leadership roles could be empowering; while for another to be able to attend meetings and share their opinions could be empowering. Various organizations concluded that it would be best to continue in their attempts anchored around letting women farmers define what empowerment meant for them, while working on creating better measurement tools and program designs that truly shifts and equalizes power.

The second round table highlighted the deep and expansive work being undertaken with women farmers and women’s collectives in the realm of empowerment. The practitioners elaborated the challenges they faced while working on interventions rooted in empowerment. The challenges led the organizations to rely on economic indicators in their respective interventions. Insights from practitioners highlighted the need to build capacities of women farmers to undertake data-backed business planning and decision making as well as devise strategies to enhance collective agency and critical consciousness to scale empowerment. The floor acknowledged that the content and interventions for women farmers should be mindful of diversity in their contexts and languages with a focus on human mediated delivery while at the same time focussing on simplifying solutions and products. Further emphasis needs to be placed on closing the gender gaps in access to digital resources with creating women centered products that are conscious of women’s unique needs and capabili

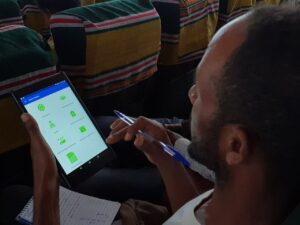

The second round table highlighted the deep and expansive work being undertaken with women farmers and women’s collectives in the realm of empowerment. The practitioners elaborated the challenges they faced while working on interventions rooted in empowerment. The challenges led the organizations to rely on economic indicators in their respective interventions. Insights from practitioners highlighted the need to build capacities of women farmers to undertake data-backed business planning and decision making as well as devise strategies to enhance collective agency and critical consciousness to scale empowerment. The floor acknowledged that the content and interventions for women farmers should be mindful of diversity in their contexts and languages with a focus on human mediated delivery while at the same time focussing on simplifying solutions and products. Further emphasis needs to be placed on closing the gender gaps in access to digital resources with creating women centered products that are conscious of women’s unique needs and capabili ties. Digital access is a right, and safe spaces should be created to increase technology adoption among women farmers.

ties. Digital access is a right, and safe spaces should be created to increase technology adoption among women farmers.

For the third roundtable session, research organizations such as ICRISAT, IFPRI, IRRI, and ISST deliberated on the frameworks and indicators that they have developed to measure women farmers’ economic empowerment. The panel discussed the critical need to view women farmers as a heterogenous group wherein empowerment can not be prescriptive. They acknowledged that measuring empowerment, given its complexity and subjectivity, relying only on quantitative indicators alone posed a critical challenge. The panel highlighted the use of PRO-WEAI & ANEW tools that measure empowerment through intrinsic, instrumental, and collective agency channels. The panelists emphasized the importance of robust qualitative studies to complement quantitative tools based on field experiences. The panel agreed that measuring empowerment requires a mixed-method approach that combines qualitative and ethnographic insights to strengthen quantitative indicators and provide nuanced insights.

The day concluded with an agreement that the grassroot level networks and collaborations must be tapped in to reach the last mile to provide women farmers with access to technology, resources and knowledge. This further requires a convergence among eco-systems including practitioners, experts, researcher organizations as well as private players for collaborative solutions and interventions devised for women farmers.

Digital Green envisioned this event as an ongoing co-learning space that will enable us to hold regular deep dialogues and form an expert group with like-minded organizations. These dialogues will be geared to build a shared vision and strategy for empowerment of women farmers; a space for collaborative learning to use collective power towards making a sincere shift in the lives of the women farmers.

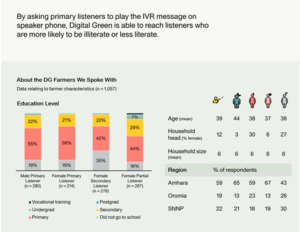

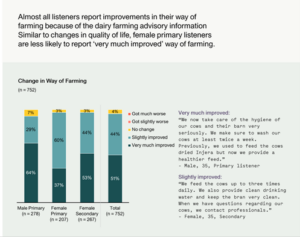

The study included interviews with 1,057 dairy farmers in Ethiopia who received advisory messages through the 8028 IVR calls, of which 59% were from the Amhara region. The samples were segmented between primary, secondary, and partial listeners based on their listening rate of the 5 advisory messages delivered through the IVR. Of the interviewed farmers, 41% reported that their quality of life has very much improved due to the IVR service they are getting, of which 28% mentioned that their dairy production has increased, and 19% said they have become able to afford household bills. Listeners valued convenience, ease of understanding, and usefulness of the information.

The study included interviews with 1,057 dairy farmers in Ethiopia who received advisory messages through the 8028 IVR calls, of which 59% were from the Amhara region. The samples were segmented between primary, secondary, and partial listeners based on their listening rate of the 5 advisory messages delivered through the IVR. Of the interviewed farmers, 41% reported that their quality of life has very much improved due to the IVR service they are getting, of which 28% mentioned that their dairy production has increased, and 19% said they have become able to afford household bills. Listeners valued convenience, ease of understanding, and usefulness of the information.  About 9 in 10 male farmers applied information, compared to only 7 in 10 female farmers. Similarly, close to 8 in 10 male farmers use AI services for crossbred cattle, compared to only 65% of female listeners. According to the study, levels of decision-making ability vary by sex and listener groups, and sharing information is also likely to be between members of the same sex in a community forum. Male listeners are more likely to share information through family gatherings than females, while female listeners are more likely to share the information in one-to-one conversations and village-level community groups compared to males.

About 9 in 10 male farmers applied information, compared to only 7 in 10 female farmers. Similarly, close to 8 in 10 male farmers use AI services for crossbred cattle, compared to only 65% of female listeners. According to the study, levels of decision-making ability vary by sex and listener groups, and sharing information is also likely to be between members of the same sex in a community forum. Male listeners are more likely to share information through family gatherings than females, while female listeners are more likely to share the information in one-to-one conversations and village-level community groups compared to males.  The study also indicated that the project could consider providing messaging around joint decision-making to increase female levels of decision-making ability in the household. The IVR messages should reinforce the need for more equitable distribution of dairy activities within households. Besides female reach, the study recommends additional assistance to deepen the impact of the IVR messaging including encouraging and incentivizing women to share messages with other women in their households and community to increase the impact on farmers not just by interacting with them directly, but also through their family members. Improving women farmers’ access to financial products could increase the adoption of AI to get crossbred cattle and in turn, potentially increase IVR’s effectiveness is also recommended by the study.

The study also indicated that the project could consider providing messaging around joint decision-making to increase female levels of decision-making ability in the household. The IVR messages should reinforce the need for more equitable distribution of dairy activities within households. Besides female reach, the study recommends additional assistance to deepen the impact of the IVR messaging including encouraging and incentivizing women to share messages with other women in their households and community to increase the impact on farmers not just by interacting with them directly, but also through their family members. Improving women farmers’ access to financial products could increase the adoption of AI to get crossbred cattle and in turn, potentially increase IVR’s effectiveness is also recommended by the study.

mily. In a refresher and planning meeting at Tantnagar block of West Singhbhum district with all the block officials, cadres, and farmers, she happily shared her experience and said that: “I have learned from the video advisory on potato crop and tried it on a small scale to see the difference from traditional farming and I am surprised to see that my potato crop is healthy and grows very fast, where in just a week time the growth is parallel to one-month crop with traditional farming. The yield is also higher which I can compare to the production cost. On my main crop field, I have not treated the seeds and used chemical fertilizers and pesticides for better growth and yield but in my small

mily. In a refresher and planning meeting at Tantnagar block of West Singhbhum district with all the block officials, cadres, and farmers, she happily shared her experience and said that: “I have learned from the video advisory on potato crop and tried it on a small scale to see the difference from traditional farming and I am surprised to see that my potato crop is healthy and grows very fast, where in just a week time the growth is parallel to one-month crop with traditional farming. The yield is also higher which I can compare to the production cost. On my main crop field, I have not treated the seeds and used chemical fertilizers and pesticides for better growth and yield but in my small  Similarly, a woman frontline worker named Gudiya, from Chitarpur block in Ramgarh district, who is the Aajeevika Krishak Sakhi (AKS) in Murubanda village is sharing knowledge on agricultural activities with farmers through videos. She spoke in a cadres meeting that this new digital technology has made her work easier. More farmers are now understanding, believing in the video advisories, and adopting them, which before was difficult by giving verbal training at community meetings, and also there was the extra effort of needing to explain all the advisories in practical terms. Now, farmers are also demanding other farming videos to be shown in the meeting as they found these videos interesting and relevant to their work. As a result, Gudiya is disseminating these videos in more community meetings and gatherings, and gaining respect among community members.

Similarly, a woman frontline worker named Gudiya, from Chitarpur block in Ramgarh district, who is the Aajeevika Krishak Sakhi (AKS) in Murubanda village is sharing knowledge on agricultural activities with farmers through videos. She spoke in a cadres meeting that this new digital technology has made her work easier. More farmers are now understanding, believing in the video advisories, and adopting them, which before was difficult by giving verbal training at community meetings, and also there was the extra effort of needing to explain all the advisories in practical terms. Now, farmers are also demanding other farming videos to be shown in the meeting as they found these videos interesting and relevant to their work. As a result, Gudiya is disseminating these videos in more community meetings and gatherings, and gaining respect among community members.

got 24 kg of black mustard seeds at a 100% subsidized rate under the National Food Security Mission and targeted for more yield than earlier, so after seeds distribution to farmers; the block team and AKS of that village decided to do group farming in a patch of 5.5 acres of land as the plots of those farmers are nearby and chose to adopt the CSA video advisories for mustard farming. They found it easier to do all the farming-related activities on time and convenient to look after the crop properly. This group farming also gave confidence to farmers to bear the minimum loss and do their work effectively with the help of each other, see the difference from traditional farming methods, and the impact of these advisories on the ground. They did all the practices starting from a seed treatment with Beejamrit, land preparation, line sowing, weeding, disease, and pest management using natural fertilizers and pesticides, and timely irrigation from Jeevamrit until harvesting, as had been shown in the video.

got 24 kg of black mustard seeds at a 100% subsidized rate under the National Food Security Mission and targeted for more yield than earlier, so after seeds distribution to farmers; the block team and AKS of that village decided to do group farming in a patch of 5.5 acres of land as the plots of those farmers are nearby and chose to adopt the CSA video advisories for mustard farming. They found it easier to do all the farming-related activities on time and convenient to look after the crop properly. This group farming also gave confidence to farmers to bear the minimum loss and do their work effectively with the help of each other, see the difference from traditional farming methods, and the impact of these advisories on the ground. They did all the practices starting from a seed treatment with Beejamrit, land preparation, line sowing, weeding, disease, and pest management using natural fertilizers and pesticides, and timely irrigation from Jeevamrit until harvesting, as had been shown in the video.

Farmers from Balumath block in Latehar district shared that they are now easily adopting NPM practices with the help of video advisories disseminated in their community meetings and facilitated effectively by AKSs. As the NPM practices have been promoted for years by the government, AKSs used to share the knowledge with farmers in their respective villages but every time a farmer decided to adopt this, AKSs had to prepare those organic manures and pesticides for them to understand the full method. But after the video advisories were implemented, most of the farmers adopted these NPM practices just after watching the videos and when additional support is needed in preparing these, they just watch the videos again on their smartphones and do it. Only those farmers who don’t have access to smartphones are seeking help from AKSs and other neighbour farmers who have adopted this earlier.

Farmers from Balumath block in Latehar district shared that they are now easily adopting NPM practices with the help of video advisories disseminated in their community meetings and facilitated effectively by AKSs. As the NPM practices have been promoted for years by the government, AKSs used to share the knowledge with farmers in their respective villages but every time a farmer decided to adopt this, AKSs had to prepare those organic manures and pesticides for them to understand the full method. But after the video advisories were implemented, most of the farmers adopted these NPM practices just after watching the videos and when additional support is needed in preparing these, they just watch the videos again on their smartphones and do it. Only those farmers who don’t have access to smartphones are seeking help from AKSs and other neighbour farmers who have adopted this earlier.  video-based crop advisories in her village-level community meetings. She shared that after using these digital tools for video advisories the adoption has increased among farmers: “As the advisory is localized and time specific, farmers found it authentic and easy to understand and this has built a self-confidence in me to do my work more efficiently.” Where before she was approaching farmers individually to give crop advisory and adoption by them, and now farmers are calling her to visit their crop fields and see the benefits of adoption.

video-based crop advisories in her village-level community meetings. She shared that after using these digital tools for video advisories the adoption has increased among farmers: “As the advisory is localized and time specific, farmers found it authentic and easy to understand and this has built a self-confidence in me to do my work more efficiently.” Where before she was approaching farmers individually to give crop advisory and adoption by them, and now farmers are calling her to visit their crop fields and see the benefits of adoption.

Rural community members and farmers from 3 different districts in Jharkhand (West Singhbhum, Gumla, and Simdega) have been trained in video production modules and become Video Resource Persons (VRPs) who are producing community videos on improved agricultural practices. These VRP team members also shared that they are happy and excited to produce videos, which would further be used in community training. They are proud that they would be contributing to the knowledge transfer of best practices to the farmers for better yield and income, which they will be documenting. This new work is encouraging and exciting for them, where they could not even come out of their home for work, now they are traveling to different villages for shooting, meet with new people and even convincing them to provide their time and work as actors in the videos. They are now confident about continuing with their work and producing videos on Climate Smart Agriculture (CSA) and Sustainable Agriculture (SA) practices.

Rural community members and farmers from 3 different districts in Jharkhand (West Singhbhum, Gumla, and Simdega) have been trained in video production modules and become Video Resource Persons (VRPs) who are producing community videos on improved agricultural practices. These VRP team members also shared that they are happy and excited to produce videos, which would further be used in community training. They are proud that they would be contributing to the knowledge transfer of best practices to the farmers for better yield and income, which they will be documenting. This new work is encouraging and exciting for them, where they could not even come out of their home for work, now they are traveling to different villages for shooting, meet with new people and even convincing them to provide their time and work as actors in the videos. They are now confident about continuing with their work and producing videos on Climate Smart Agriculture (CSA) and Sustainable Agriculture (SA) practices.

Emuye Muche, a 40 years old resident of Korata Kebele in Ethiopia is a mother of five children whose livelihood depends on the agricultural products she gets from her one acre of land, one cow, and five hens. Emuye started attending video dissemination sessions back in 2021 when the Development Agent set the session for the development group she is a part of at her house. Since then, Emuye has attended video dissemination sessions on poultry production, vermicomposting, maize side dressing, maize sowing, compost, urea molasses block preparation, PICS bag, nutrition, and vegetable production. She said: “what changed my life is the vermicompost preparation training, which was my first practice in video extension. I was surprised with the produced compost displayed in the video, which had a very attractive dark brown color like roasted coffee powder, my favorite powder. I learned from the video that it can replace Urea fertilizer, which is useful for vegetable and other crop productions. I learned that the production bed was prepared with local material at a shadowy place to prevent direct sunlight and predator birds from eating the worms. I also understood that all the materials for this compost preparation are not from outside of our area but are locally available materials.” home.”

Emuye Muche, a 40 years old resident of Korata Kebele in Ethiopia is a mother of five children whose livelihood depends on the agricultural products she gets from her one acre of land, one cow, and five hens. Emuye started attending video dissemination sessions back in 2021 when the Development Agent set the session for the development group she is a part of at her house. Since then, Emuye has attended video dissemination sessions on poultry production, vermicomposting, maize side dressing, maize sowing, compost, urea molasses block preparation, PICS bag, nutrition, and vegetable production. She said: “what changed my life is the vermicompost preparation training, which was my first practice in video extension. I was surprised with the produced compost displayed in the video, which had a very attractive dark brown color like roasted coffee powder, my favorite powder. I learned from the video that it can replace Urea fertilizer, which is useful for vegetable and other crop productions. I learned that the production bed was prepared with local material at a shadowy place to prevent direct sunlight and predator birds from eating the worms. I also understood that all the materials for this compost preparation are not from outside of our area but are locally available materials.” home.” activity. The first thing we did was collect cow dung from the field. Then, I prepared the composting bed in my backyard and brought the worms to start and manage them. I remember that the initial numbers of worms that I used were 22 in number but thanks to God, I currently have thousands, and recently, I distributed them to 12 farmers who are willing to adopt the practice.”

activity. The first thing we did was collect cow dung from the field. Then, I prepared the composting bed in my backyard and brought the worms to start and manage them. I remember that the initial numbers of worms that I used were 22 in number but thanks to God, I currently have thousands, and recently, I distributed them to 12 farmers who are willing to adopt the practice.”

International Youth Day 2022

International Youth Day 2022 ikish Bogale lives in Hadiya Zone Lemo Woreda. After her husband passed away, her life changed drastically. Before, she dedicated her time to the household and her six children while her husband managed their one hectare farm, growing bean, wheat, barley, and maize. Her husband used to be an active member of a development group in the area, but Sinafikish had not been involved. After her husband’s passing, Sinafikish began taking a more active role in the farm. She said, “I decided to engage myself in farming. I started communicating with the development agents of my village and actively started attending video dissemination sessions. Even if I did not have prior knowledge and practice of how to prepare land, sowing, harvesting, I have gotten practical knowledge about wheat growing from the video dissemination sessions that I have attended in women development groups.”

ikish Bogale lives in Hadiya Zone Lemo Woreda. After her husband passed away, her life changed drastically. Before, she dedicated her time to the household and her six children while her husband managed their one hectare farm, growing bean, wheat, barley, and maize. Her husband used to be an active member of a development group in the area, but Sinafikish had not been involved. After her husband’s passing, Sinafikish began taking a more active role in the farm. She said, “I decided to engage myself in farming. I started communicating with the development agents of my village and actively started attending video dissemination sessions. Even if I did not have prior knowledge and practice of how to prepare land, sowing, harvesting, I have gotten practical knowledge about wheat growing from the video dissemination sessions that I have attended in women development groups.” Back in 2019, Ermisa Dindo, a resident of Damboya woreda, used to think of a video-based extension was a waste of time. But he gave it a chance, and now Ermisa is an active attendee of video dissemination sessions. He adopts each practice to the extent possible. Ermisa explains, “I started to practice Teff and wheat row planting after watching the videos. Adopting these practices saved the seed rates and the fertilizer amount per hectare, and there is also a yield difference in the produces. I would also like to diversify my income through cattle farming by improving and crossbreeding local cattle as well as producing vegetable crops.”

Back in 2019, Ermisa Dindo, a resident of Damboya woreda, used to think of a video-based extension was a waste of time. But he gave it a chance, and now Ermisa is an active attendee of video dissemination sessions. He adopts each practice to the extent possible. Ermisa explains, “I started to practice Teff and wheat row planting after watching the videos. Adopting these practices saved the seed rates and the fertilizer amount per hectare, and there is also a yield difference in the produces. I would also like to diversify my income through cattle farming by improving and crossbreeding local cattle as well as producing vegetable crops.”

During a field visit to Jharkhand, we were able to interact with two producer groups in Namkum and Latehar, that were previously women’s self-help groups, and get a glimpse into their journey to where they are now. More than individual women farmers becoming champions of change within these respective communities, what was evident was the power of collective agency. These producer groups have become a pillar of support whenever these women need support with input mobilization, capacity building, knowledge sharing, and product aggregation etc. Coming together, these women farmers recognize that working collectively is helping them enhance their leadership skills and realize the economies of scale.

During a field visit to Jharkhand, we were able to interact with two producer groups in Namkum and Latehar, that were previously women’s self-help groups, and get a glimpse into their journey to where they are now. More than individual women farmers becoming champions of change within these respective communities, what was evident was the power of collective agency. These producer groups have become a pillar of support whenever these women need support with input mobilization, capacity building, knowledge sharing, and product aggregation etc. Coming together, these women farmers recognize that working collectively is helping them enhance their leadership skills and realize the economies of scale.  Participatory videos have played a significant role in empowering women farmers with knowledge, and building their confidence and ownership in being a part of producer groups. A frontline worker (FLW) reflected,

Participatory videos have played a significant role in empowering women farmers with knowledge, and building their confidence and ownership in being a part of producer groups. A frontline worker (FLW) reflected,  The enterprising vision was especially evident in our interaction with the producer group that we met in Latehar, Jharkhand. This is a producer group that was formed in 2016, and they have been trained and mobilized on this front. When asked about how they bifurcate and sell their produce, they had a clear response –

The enterprising vision was especially evident in our interaction with the producer group that we met in Latehar, Jharkhand. This is a producer group that was formed in 2016, and they have been trained and mobilized on this front. When asked about how they bifurcate and sell their produce, they had a clear response –

ng to advance the livelihoods, resilience and self-determination in the Adivasi tribe communities, and foster the recovery from the economic effects of COVID-19 by strengthening women farmer producer organisations and their bargaining power.

ng to advance the livelihoods, resilience and self-determination in the Adivasi tribe communities, and foster the recovery from the economic effects of COVID-19 by strengthening women farmer producer organisations and their bargaining power.

Sabita Devi

Sabita Devi