In my use of human-centered design (HCD) at Digital Green, I found that the inspiration and ideation phase in HCD as being completely intertwined. They can’t really be separated into two neatly divided phases. While we were trying to find a solution to the question ‘How can we enable field level workers to operate equipment confidently?’ – the processes we followed seemed to make no sense initially. In my previous blog, I had mentioned that it was the ‘messiness’ of the process that I really started enjoying, once I stopped being so hung up about ‘being systematic’. In that, what I both enjoyed and learnt the most was the freedom to follow your intuition and develop your own versions of methods, activities and processes.

While we used several of the conventional methods, such as interviews and secondary research, we also designed and conducted activities with users that we felt would get us closer to our design principles, and the solution. They could largely be bunched under 2 categories:

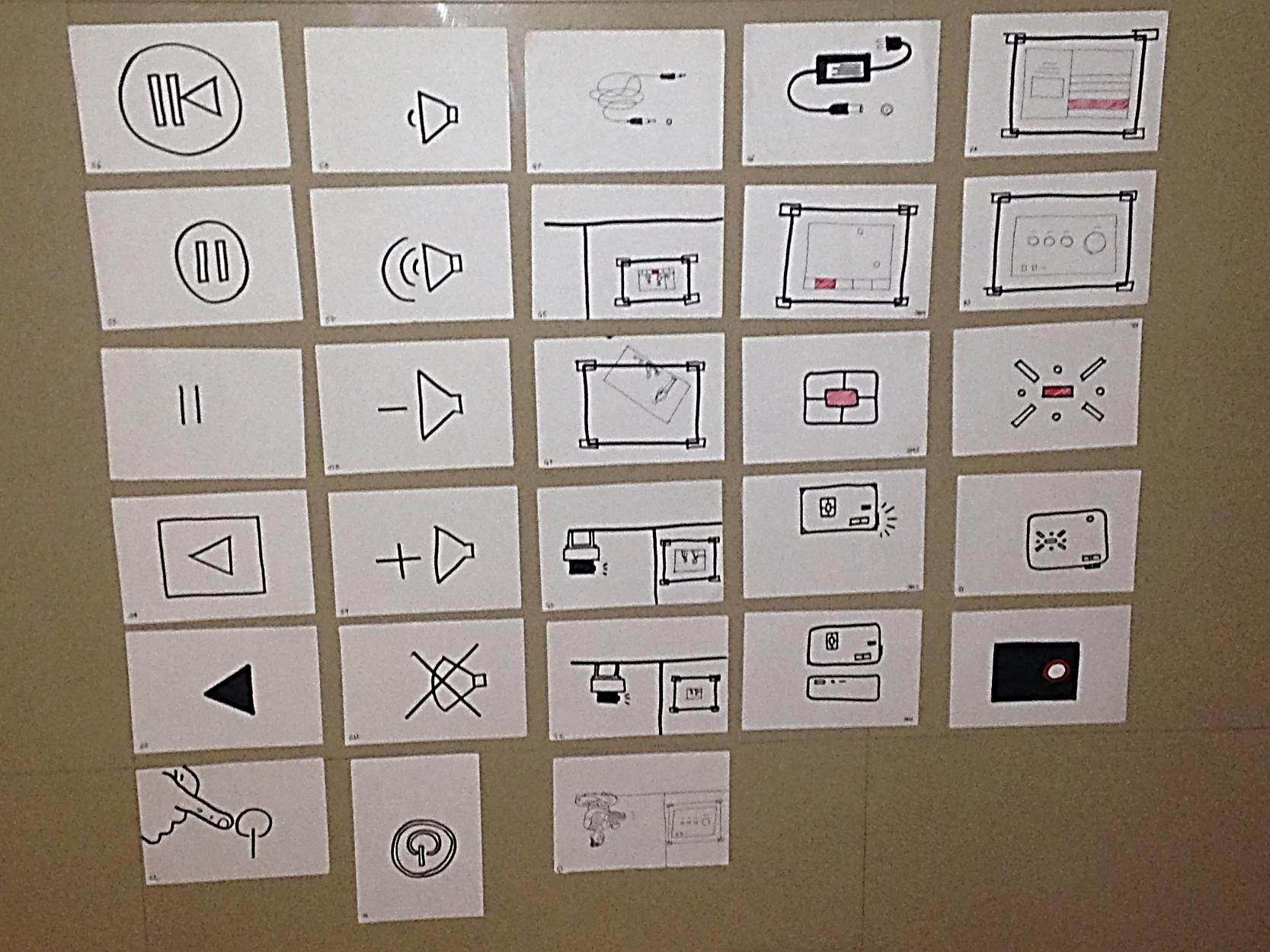

- Sharing what they know: We wanted our users, the field level workers, to learn the technical aspects of equipment operation really well. Therefore, it was important to understand the current experience and knowledge levels. What they shared revealed some very interesting insights. For example, that their ‘visual language’ was very different than ours. Or symbols on equipment, which we take for granted, is complex for them. They understood illustrations which show the context better than abstract symbols.

- Sharing their perspective: As trainers, we tend to see the learning process from our perspective and it is quite difficult to know the perspective of a person who learns differently from us. We saw this difference and wanted to understand from the field-level workers what is necessary for them to learn and how the learning process can be made easier. To reach there, we asked them to demonstrate how they would have made their peers learn, which revealed some critical aspects in their learning, for instance, the verbal language used in training – they used different terms to explain things than our trainers.

Under the above two categories, we conducted several activities, some of which used ‘co-creation’. I am using the term co-creation to define a process in which the end user creates at least some part of the prototype. It is a concept, not a tool or a method. Several methods can use the concept of co-creation. It could be a role-play that the users develop along with the designer, or a script for which they provide dialogues.

Participatory Video techniques and Co-creation

Of the different methods, I focus on participatory video here. Working with any participatory process, including video production, teaches you to learn from those who are at the center of the issue. Participatory video production is supposed to be driven by communities to communicate what they want to, and in a manner that they want. In co-creation models, though the user community is involved in the creation of a prototype/solution, they are usually not the ones driving it. Further, they communicate what the designer wants them to communicate. To make it more tangible, through participatory videos a community could have made a video about any issue they cared about. But as part of co-creation, we, the designers, asked them to make a video story specifically about equipment operation. The agenda was driven by us, not them.

Our team combined these two seemingly similar, but actually different concepts. We created several prototypes for different solutions that can together improve the training. The possible solutions included a training video, an illustrative handout and a team game that also works as a skill assessment. Initially, we thought that an obvious prototype of a video would be a role-play or a script. But then we thought – we have all the equipment and experience to make a video quickly. So, when prototyping, we used participatory video techniques for co-creation of a video. We asked the field level workers to develop the content for the video, which would show their peers how the equipment works. When they discussed the story with us, they had:

- Developed characters – who should be training whom (a senior field level worker will train a new joiner)

- Decided the context – when does one need the learning support (users usually find it difficult to operate equipment at the beginning),

- Defined the content – what are the essential operations to be learnt (a 15 step process)

We shot the prototype video with them, edited it the same evening and tested it the next day in a meeting of field level workers. Interestingly, most of the feedback that we got was related to the audio and light quality. Pretty much everything else worked. We made some basic changes, developed another version and tested that too, to come to a version – one both the users and us were happy with. We used the same process for two other training videos, where users even shot the video (though they did not edit it), and both times the results were the same. Very clearly, the users were the best creators, at least in this case.

We acted just as facilitators, and the users were creating the whole framework. It definitely helped that I knew participatory video techniques well, and it was easy for me to facilitate the process of story development and shooting.

The final training video that we shot was not participatory. Professional filmmakers, who were not related to the context at all took the script and shot the video with professional actors. This was done primarily to ensure ‘quality’ since that was the major drawback of the prototype video that we created. However, it was still ‘co-created’. After all, the script, though modified to some extent, was developed by the users.

The use of these different methods for research and prototyping gave us some strong design principles that kept us in good stead as we made several training videos over the course of 2 years. You can watch the training videos that we made on pico operation, documentation and video production here.

Do you know of designers who’ve used participatory techniques and/or processes in their design research? Have you used it yourself? I would definitely be interested to know more about your experiences in bringing together participatory videos and HCD together.

These issues are very similar to those a qualitative researcher faces when developing her/his research question. One benefit of designing a challenge within an organization is that at the beginning itself you might have a very good sense of the impact that you want to have. Whereas an academic researcher is not looking at impact per se, but at the knowledge and learning that the research can help create. And, therefore, this process could be much more ambiguous for her. At the same time, working in an organizational context can limit you right at the beginning. I personally felt so caught in thoughts like, ‘But this is not how things happen at DG’, ‘But others will never be open to this’, ‘Oh, it is going to be so difficult to implement something like this.’ Before we could free ourselves to be ‘creative’ and ‘innovative’, we were binding ourselves. What helped us to get through the process was:

These issues are very similar to those a qualitative researcher faces when developing her/his research question. One benefit of designing a challenge within an organization is that at the beginning itself you might have a very good sense of the impact that you want to have. Whereas an academic researcher is not looking at impact per se, but at the knowledge and learning that the research can help create. And, therefore, this process could be much more ambiguous for her. At the same time, working in an organizational context can limit you right at the beginning. I personally felt so caught in thoughts like, ‘But this is not how things happen at DG’, ‘But others will never be open to this’, ‘Oh, it is going to be so difficult to implement something like this.’ Before we could free ourselves to be ‘creative’ and ‘innovative’, we were binding ourselves. What helped us to get through the process was:

At that time the price of the crop increases from INR 10 per kg to about INR 100 per kg, making it quite lucrative for farmers. The price, of course, depends on the market, and the key to realizing a good profit is information on the rates in different markets – and this is exactly what the LOOP app facilitates. I learned that before being part of the LOOP project, farmers normally went to the Pune flower market where they got a rate of about INR 45 – 50 per kg during peak season. This is almost half of their INR 80 per kilo earning from a four-day sale of flowers in Mumbai through LOOP. With an additional net profit of INR 350,000 from the sale, farmers were more than thrilled to be a part of the program. In fact, one among those farmers chose not sell his flowers with the others, and realized a price of INR 45 per kg only, losing out on the additional profit. From this experience, now these farmers are tapping markets for other crops they grow. Recently, they made a sale of inferior quality raw bananas in one of Mumbai’s chips making value chain, instead of the Panghat market where they usually went.

At that time the price of the crop increases from INR 10 per kg to about INR 100 per kg, making it quite lucrative for farmers. The price, of course, depends on the market, and the key to realizing a good profit is information on the rates in different markets – and this is exactly what the LOOP app facilitates. I learned that before being part of the LOOP project, farmers normally went to the Pune flower market where they got a rate of about INR 45 – 50 per kg during peak season. This is almost half of their INR 80 per kilo earning from a four-day sale of flowers in Mumbai through LOOP. With an additional net profit of INR 350,000 from the sale, farmers were more than thrilled to be a part of the program. In fact, one among those farmers chose not sell his flowers with the others, and realized a price of INR 45 per kg only, losing out on the additional profit. From this experience, now these farmers are tapping markets for other crops they grow. Recently, they made a sale of inferior quality raw bananas in one of Mumbai’s chips making value chain, instead of the Panghat market where they usually went.

Another farmer M.V. Subba Rao from East Godavari district has been looking for literature and relevant information on zero-budget natural farming and pointed out that Digital Green extension system will be helpful to farmers in his community. Gundra Ambayya, a smallholder farmer from V.Kothapalli village in East Godavari district requested that we transfer the videos on natural farming methods onto his mobile phone – which we did with pleasure. While watching a video on natural farming method for cultivating tomatoes, one farmer asked us “Why did they put a stick as a support for the tomato plant?” He wanted to watch more such videos on vegetable cultivation. Many Agriculture Sciences students were also fascinated by the videos and agreed that it’s a good way to reach many farmers.

Another farmer M.V. Subba Rao from East Godavari district has been looking for literature and relevant information on zero-budget natural farming and pointed out that Digital Green extension system will be helpful to farmers in his community. Gundra Ambayya, a smallholder farmer from V.Kothapalli village in East Godavari district requested that we transfer the videos on natural farming methods onto his mobile phone – which we did with pleasure. While watching a video on natural farming method for cultivating tomatoes, one farmer asked us “Why did they put a stick as a support for the tomato plant?” He wanted to watch more such videos on vegetable cultivation. Many Agriculture Sciences students were also fascinated by the videos and agreed that it’s a good way to reach many farmers.

s organic pesticide on all his crops. He also continues to attend the video screenings to learn new methods.

s organic pesticide on all his crops. He also continues to attend the video screenings to learn new methods.