Each Story Brings Change

Munnawar is a 42 year old ASHA (Accredited Social Health Activist) worker hailing from a Muslim family in Banera which is one of the Muslim dominant villages of Naarsan block, in Uttarakhand state in North India. She has four daughters and four sons, and her husband works as an agricultural laborer – they both work hard to ensure that their children obtain formal education which they were not able to as they did not have the means. Despite this, Munnawar has gone on to become one of the most well-known ASHA workers in her community, catering to more than 1400 families, because of how well she connects with mothers and their families.

Prior to becoming an ASHA worker, she worked under a private doctor as a birth attendant, and assisted an ASHA worker in her village in carrying out scheduled health activities. By virtue of this engagement, she learned more about the role that an ASHA worker plays.

Noticing her work, in 2012, the village head Mr. Salim recommended Munawwar for the position of an ASHA worker in the village despite not being literate. Her limited exposure to formal education posed a barrier to being able to maintain records and reporting work, but her coworkers were supportive. In return, Munawwar assisted her coworkers by accompanying them for home visits especially for counseling families who were adamant on their traditional beliefs about mother and child care.

Over the years, Munawwar has gained the confidence to be able to support families within their communities and change their beliefs about ill-informed maternal and child health practices. She has worked diligently with families and has counseled mothers so that they can go for safer health and nutrition practices. By using digital methods that she learned about through Digital Green’s capacity building workshops on video production, training and dissemination, she has been able to share knowledge about institutional delivery, immunization, and modern family planning methods.

Even after all this time, she still ensures that she goes for daily home visits and that all necessary support is given to families at any point of time. Her level of care towards mothers has extended to the point where once a mother had a delivery complication, she even donated her blood to save her life. Her dedication has cemented her position as an influencer within her community. During the pandemic, she kept at it by sharing videos via Whatsapp, and continuing to support families for anything that they needed.

Even after all this time, she still ensures that she goes for daily home visits and that all necessary support is given to families at any point of time. Her level of care towards mothers has extended to the point where once a mother had a delivery complication, she even donated her blood to save her life. Her dedication has cemented her position as an influencer within her community. During the pandemic, she kept at it by sharing videos via Whatsapp, and continuing to support families for anything that they needed.

Frontline workers like Munnawar are the agents of change, and serve as the interface between health systems and structures, and community members to ensure their health and wellbeing. They have been integral to the overall success of Project Samvad. Similar to Munnawar’s story of perseverance and dedication, Project Samvad has been able to work with over 5,000 ASHA and Anganwadi workers across six states in India, to build their capacities on using digital approaches to share knowledge and connect with their respective communities. Resilient frontline workers at the grassroots level reflect all the more on the effectiveness of health system structures in being able to reach and impact communities in rural and remote areas. Project Samvad has significantly contributed to our learnings on gender and resilience.

What made Project Samvad so unique?

Health is never just physical, it is also about growing up in a healthy household that allows a child to feel loved, secure, and physically healthy. In our society, more than anyone else, mothers are responsible for caring for the wellbeing of their children, and raising them in a healthy household, and so they must be educated and made aware of optimal health and nutrition practices. To build a truly equitable society, women must be allowed to have agency on how they plan out their families and futures.

Health is never just physical, it is also about growing up in a healthy household that allows a child to feel loved, secure, and physically healthy. In our society, more than anyone else, mothers are responsible for caring for the wellbeing of their children, and raising them in a healthy household, and so they must be educated and made aware of optimal health and nutrition practices. To build a truly equitable society, women must be allowed to have agency on how they plan out their families and futures.

When we say that information is power today, what we mean is not the bulk or abundance of information, but how the needed information reaches a person in the remotest area of a poor, developing, and yet a hopeful country that enables him or her to make an informed choice which has the power to transform lives.

Similarly, Project Samvad has not just been about sharing information through digital approaches, but how this method of sharing information, and the knowledge in itself can transform the communities that we have worked in for the past six years, and give them the hope for a better and healthier tomorrow. For example, by simply sharing an instructional video with targeted women in the community via Whatsapp, it is not just the availability of the content but the fact that at any given moment, it will only take a click of a button to access information that can change the quality of life of these women and children.

Similarly, Project Samvad has not just been about sharing information through digital approaches, but how this method of sharing information, and the knowledge in itself can transform the communities that we have worked in for the past six years, and give them the hope for a better and healthier tomorrow. For example, by simply sharing an instructional video with targeted women in the community via Whatsapp, it is not just the availability of the content but the fact that at any given moment, it will only take a click of a button to access information that can change the quality of life of these women and children.

“We never let go of the hope, the heart, and the pulse of the community” is what Dr Sangita Patel, Health Director of USAID shared in the last dissemination workshop that was held by the Project Samvad team on 9th February. Community-centered approaches with the value-addition of digital technologies have always rung true for Digital Green across interventions in Health, Nutrition, Gender, and Agriculture. Collective learnings from Samvad continue to inform our approach towards community engagement, social-behavioral change communication, and hybrid digital approaches that have transformative potential.

Impact in Numbers

Project Samvad had a massive impact across six states in India, namely Uttarakhand, Bihar, Jharkhand, Odisha, Chhattisgarh, and Assam. Looking back, the Project has reached over 700,000 women directly, and 360,000 women have been using digital channels.

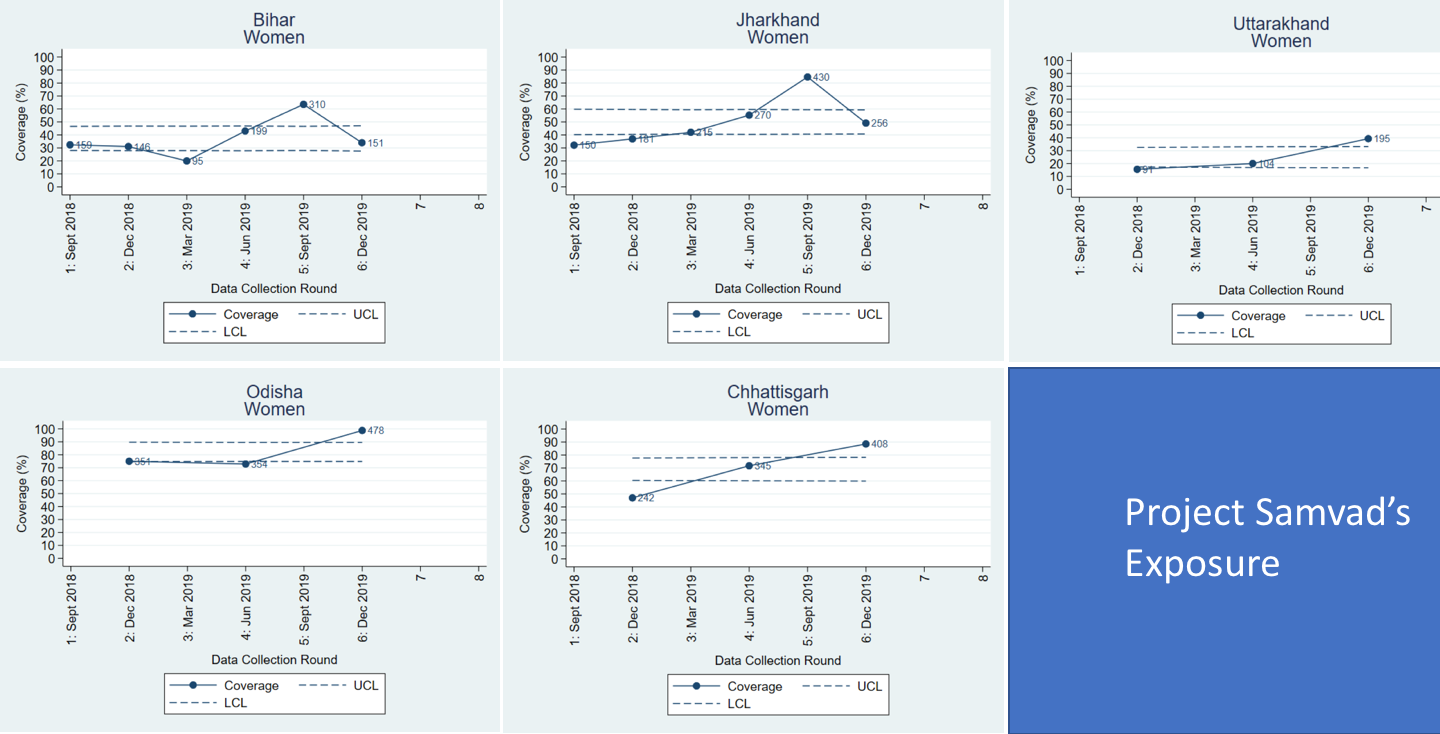

During the project implementation period, the exposure of women to digital dissemination channels gradually increased from 32% in July 2018 to 96% by December 2018. From the first survey conducted in September 2018 to the latest one in January 2020, the percentage of women and men who knew at least three different modern family planning methods grew from 39.1% to 76.3%.

During the project implementation period, the exposure of women to digital dissemination channels gradually increased from 32% in July 2018 to 96% by December 2018. From the first survey conducted in September 2018 to the latest one in January 2020, the percentage of women and men who knew at least three different modern family planning methods grew from 39.1% to 76.3%.

A Phone Survey that was conducted during Project Samvad found that 9 out of 10 respondents would watch videos that they received via Whatsapp during the pandemic.

What have we learned?

Project Samvad has generated a lot of interest and insights in its duration. Our key takeaways are that the proven community video approach complemented by other digital channels such as Whatsapp and IVRS has rapidly scaled up impact amongst local communities and can be applied to any context, sector, and geography. We have found that using technology builds an intrinsic strength at horizontal as well as vertical levels – not only do they facilitate dialogues and joint learning within the community, they also serve as an interface between health system structures and the women beneficiaries.

Project Samvad has generated a lot of interest and insights in its duration. Our key takeaways are that the proven community video approach complemented by other digital channels such as Whatsapp and IVRS has rapidly scaled up impact amongst local communities and can be applied to any context, sector, and geography. We have found that using technology builds an intrinsic strength at horizontal as well as vertical levels – not only do they facilitate dialogues and joint learning within the community, they also serve as an interface between health system structures and the women beneficiaries.

From the standpoint of influencing behavior change within people, local and contextualized information that they are familiar with, plus the delivery of information in a human-mediated, participatory approach establishes and strengthens the link between service providers and the community. This is of paramount importance to improve the uptake of any best practices shared whether it be in the health domain or even agriculture.

The data that we have gathered and the lessons that we have learned are important and will continue to enormously contribute to future opportunities in strengthening national and subnational policy actions on health, nutrition, and family planning.

Here are relevant links to Project Samvad Learnings:

For more resources on Project Samvad, please visit www.digitalgreen.org/resources-samvad

Watch the Samvad Playlist that dramatizes the human impact of Project Samvad here: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL-WsPllTgj_6kJRhe1ER-PfnZGZb81Fcu

Tracking the availability of commodities

Tracking the availability of commodities