“I often ask myself what will happen if I stopped working? When the floods came, I had to be in my field to drain the waters. When the pandemic came, I had to be there to take care of my crop and fend for my family. Droughts, floods or pandemics, we don’t quit. We cannot quit. If I quit, we have to forsake our income and there won’t be food at home. My neighbors won’t be able to work on my farm and they will lose their income. We will lose the vegetables that we grow that can feed many families. Whatever may happen to the world, we farmers can’t and don’t quit even for a day.”

These are words from Koyu, a 67-year-old farmer from my own village in Kerala who grows paddy and vegetables in his 4 acres of land. I was speaking to him over the phone. There was both anger and anguish in his words.

“You know,” he continued, “everyone takes us for granted. When everything shut down… transport, railways, postal services, banks, markets and offices including those of the government, we were the only ones working. Without any complaint or expectation. We continued to produce, we toiled. When we produce less, we earn less. When we produce more, even then we earn less.” Koyu did not mince his words while sharing his frustration.

When I had this conversation with Koyu a few weeks ago, at Digital Green we were speaking to hundreds of farmers in various states of India where we work in. As an organization working with and for small-scale farmers, it was important for us to understand how they are coping with the pandemic and associated uncertainties. We designed the survey in a way that would help us and our partners to understand specific issues faced by the farmers so that we can help them overcome the situation and recover faster. The survey report is available here.

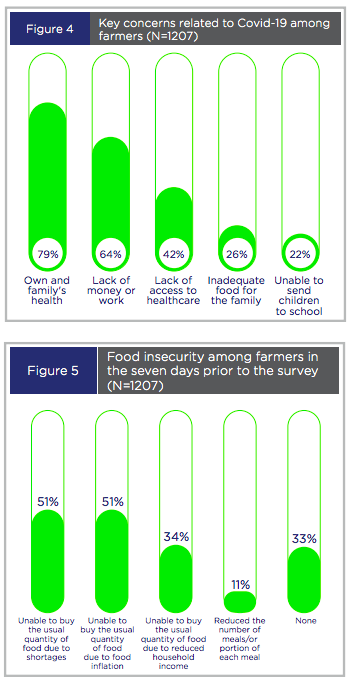

Nearly one-third of the small-scale farmers we interviewed were afraid of contracting the Coronavirus. There is widespread fear and anxiety, among both men and women, on their ability to continue production and find a market for their produce. Farmers have indeed become more vulnerable due to the pandemic. However, nearly all of them said they will grow crops for the Kharif season. Farmers are not letting the calamity deter their intent or morale.

For a society that is reeling under multiple waves of a never-seen-before humanitarian crisis that has crippled our lives, society and economy, the path to recovery can be hard and arduous. Our farmers are already playing a crucial role in that path to recovery. They are ensuring productivity, generating employment, feeding our people and most importantly regenerating the rural economy. For the country as a whole, from policymakers to practitioners, from the civil society to the common people, helping farmers at this hour means helping the economy to recover faster and build back better.

While there are many concerns the survey brought to light and require immediate attention, the survey findings also point towards some important future considerations. Of these, there are three that I want to highlight, so that future pandemics, calamities, shocks and stressors do not derail our decades of development investment.

#Power2choose: Reimagining farmers’ advisories

Let us not treat farmers are mere recipients of aid and subsidies who are supposed to till and toil for society. Time has come to accord them the importance they deserve as active partners and participants in the development process. Let us empathize with farmers and bank upon their immense wisdom, patience and resilience. To help achieve that, farmers need timely and efficient access to information to produce better, market better and claim reasonable realization for their efforts. Digital technology is that opportunity to empower farmers with choices to make informed decisions. Digital tools can help them access specific information that they want – what, when and how. Let them decide. Let them choose.

#markets4farmers: Reimagining markets

Today, the investment our government has made towards Digital India is slowly bearing fruits. More villages are getting connected to networks. Mobile telephony has reached every nook and corner of the country. Our data costs are among the lowest in the world. Smartphone usage is rising rapidly. Smartphones, data and digital tools can combine to bring about a radical transformation to markets. Digital connectivity can create hyperlocal market loops, connecting local producers and local consumers. Popular applications like WhatsApp and Telegram can help farmers build digital storefronts and transact with local consumers. Let digital technology build a network of farmers and farmer’s groups across the cast expanse of India. Let technology adapt to the needs of farmers than asking farmers to adapt to the technology. Let millions of interconnected farm enterprises bloom.

#FarmerFirst: Reimagining data

We have been taking our farmers for granted. They have historically lacked access to technology and information and in the modern data-driven agri-ecosystem, they don’t even understand that their own data is one of their biggest assets. Many kept mining their data while farmers also freely shared their data with many. Privacy, trust, confidentiality and security has a very different meaning in their social context and relations. The time has come for us to make them aware of the value of their data and help them make informed decisions. While global and national efforts to integrate and share data across platforms are a welcome move and in the right direction, let the first and most important guiding principle be to put farmers at the center or at the apex of such initiatives. Efforts to streamline and make data efficient will not bear desired results if it is not primarily helping farmers to improve their lives and livelihoods. Help farmers discover the primacy of their own data. Let Farmers be First.